After more than five years of construction, the long-awaited opening concludes a 15-year project for the complete redesign and reinstallation of the Museum’s superb collection of classical art. Returning to public view in the new space are thousands of long-stored works from the Metropolitan’s collection, which is considered one of the finest in the world. The centerpiece of the New Greek and Roman Galleries is the majestic Leon Levy and Shelby White Court—a monumental, peristyle court for the display of Hellenistic and Roman art, with a soaring two-story atrium.

“The New Greek and Roman Galleries are a milestone in an unprecedented building campaign—more than a dozen years in the making—to construct anew within the framework of our historic buildings, to make use of new methodologies while honoring the old, and to encourage our visitors to look at ancient art in a new way,” said Philippe de Montebello, director of the Metropolitan Museum.”

He said some of the 5,300 works previously in storage, many of them collected soon after the museum was founded in 1870, are now installed on two levels of the new galleries, located in the Lamont Wing at the southern end of the building. The art displayed was created between 900 B.C. and the early fourth century A.D., tracing the parallel stories of the evolution of Greek art in the Hellenistic period and the arts of southern Italy and Etruria, culminating in the period of the Roman Empire.

On the first floor, contiguous to the central Leon Levy and Shelby White Court on three sides, are galleries for Hellenistic and Roman art. The installation continues on the wholly redesigned mezzanine level, where galleries for Etruscan art and the Greek and Roman study collection overlook the court from two sides.

The focal point of the new galleries is the spectacular Leon Levy and Shelby White Court for Hellenistic and Roman art, which occupies an area created by the renowned architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White between 1912 and 1926. The atrium, which evoked the ambulatory garden of a large private Roman villa, has been transformed through the addition of another story and dazzling colored marble floors.

On view in the center of the court are several works that show Roman admiration for Greek culture, including the statue of Dionysus, god of wine and divine intoxication (Roman, Augustan or Julio-Claudian, 27 B.C.-A.D. 68, which is an adaptation of a fourth-century Greek statue). Two larger than life statues of Hercules face one another from either side of the court. And there is a purple stone called porphyry (from the Greek word for purple) which was especially prized for monuments and building projects in Imperial Rome.

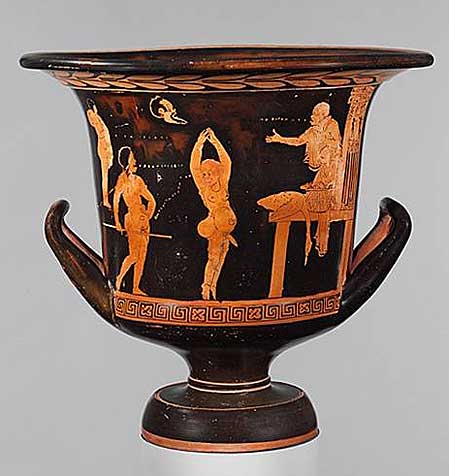

Additionally, there are thematic displays of Hellenistic art and Hellenistic funerary art, including the Marble Garland Sarcophagus, from around A.D. 200 that was found at Tarsus in southern Turkey. And the Badminton Sarcophagus from around A.D. 260 carved in high relief from a single block of marble, which shows the god Dionysus seated on a panther and surrounded by a lusty entourage of satyrs and maenads (female devotees of Dionysus).

Visible through a window in the Sardis gallery, a pair of spectacular gold serpentine armbands (Greek, Hellenistic, 200 B.C.) draws visitors into the Hellenistic Treasury, an intimate showplace for outstanding examples of luxury goods, primarily made of precious metals, gemstones or glass.

Another stunning work is a small statue of a veiled and masked dancer (Greek, third-second century B.C.) whose effect depends exclusively on the pose of the dancer and the treatment of the drapery. The woman’s face is covered with a sheer veil, which can be discerned at its edge below her hairline and at the cutouts for the eyes.

Also on view in the Hellenistic Treasury are coins and gems, as well as refined small-scale objects having a private or religious use.

The mezzanine level gallery of Etruscan art, overlooking the court, displays the mastery of the Etruscans as metalsmiths and their connection to Greek culture, as well.

The centerpiece of the Leon Levy and Shelby White Gallery for Etruscan art is one of the great works in the Museum’s collection, the newly restored, world famous Etruscan chariot (second quarter of the sixth century B.C.). One of the very few complete chariots to survive from antiquity, it is made of bronze and inlaid with precious elephant and hippopotamus ivory and depicts scenes from the life of the Greek hero Achilles.

The Homeric subject matter of the bronze chariot brings up the question of how the story of Achilles became known in Etruria, and bards may have recited the tale, although written documents may have existed, as well.

The museum already has galleries (opened in 1996) for prehistoric and early Greek arts, followed in 1999 by the opening of galleries for Archaic and Classical Greek works, and a suite of Cypriot galleries in 2000.

A new guide to the collection, Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has been published and is available at the museum and through Yale University Press. Also, a variety of education programs will be offered in conjunction with the installation of the New Greek and Roman Galleries, including lectures, gallery talks, an international symposium, a Sunday at the Met program of lectures and films, a teacher workshop, and an all-day conference for teachers.