by Dimitri C. Michalakis

“I’m an energetic person,” he explains one evening between engagements in a resonant baritone (he trained as a singer). “But because the job is demanding, and because of the many things we do, it gives me inspiration and energy.”

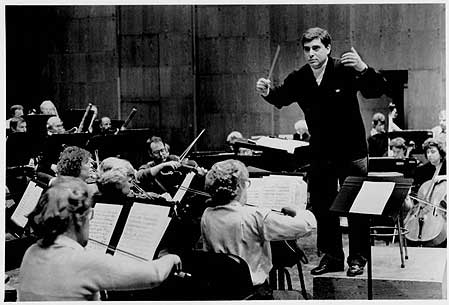

For the Society alone he conducts as many as three concerts a week, over 75 a year, but he wears many hats: he’s also dean of music at the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Manhattan and an adjunct professor at Columbia University.

“Stamina,” he says is what it takes. “It’s a multifaceted job.”

Especially being music director of the Little Orchestra with the big heart. Since his appointment in 1979, Anagnost has carried on the mandate of the group not only to revive the small ensemble of the early classical period, but also to “wrest the contemporary concert repertoire from the rut of established stereotypes with premieres of important new music and restorations of long-neglected masterpieces.”

“The Little Orchestra Society has a very distinct profile in New York and we have a very loyal audience,” he says. “We service another clientele of people.”

Last year Society audiences heard off-the-beaten-repertoire from Debussy and Ravel; the revival of a 260-year-old Vivaldi opera; and the perennial-favorite concert series for kids, Lolli-Pops (for ages 3-5) and Happy Concerts (ages 6-12), which won the George Foster Peabody Award and whose recordings were nominated for a Grammy.

“We share our excitement about the music with the children,” says Anagnost, who often dresses as the ringmaster or a candyman for a children’s concert. “I think a child comes unprejudiced to a concert and it’s up to us to show them the way and involve them. I love the phrase, ‘Involving them with our concerts.’”

And he says kids are very often the ones who make their parents regular concert goers.

“I have people in the audience that are bringing their kids, who say, ‘I never had anything like this,’ he relates. “’I never went to the concerts when I was a child.’ So what is nice about our programs for the children is that the parents are learning along with the kids.”

Through its Chance for Children program, the Society also brings great music to inner-city schools and minority youngsters. Students at Roosevelt High liked the programs so much that they bought tickets to the concerts.

“We have now created a new generation of concert goers,” Anagnost exults.

To make the experience even more accessible for kids (typical childrens’ concert series have included “Beethoven at Bat” and “Symphonosaurus Rex”), the Society features celebrity narrators, including Irene Pappas, Glenn Close, Lynn Redgrave and Claire Bloom.

“The idea is even with our adult concerts, I like to give the audience plateaus of listening,” says Anagnost. “If you give them interesting guidelines, they can appreciate it much, much more.”

As for his association with the Holy Trinity cathedral, it began 23 years ago with what has since become a traditional Candlelight Holiday Concert (done this year with the Metropolitan Singers and The Greek Choral Society), and through the Great Music under a Byzantine Dome series he initiated, has featured Byzantine music in concert with some of the most striking pieces of the modern repertoire.

“We have a lot of outsiders come because our church is so beautiful,” he says. “And they’re getting their musical education through the concert series at the Cathedral.”

Greeks, as well, especially professionals, who are a small but steady part of the audience in the concert hall.

“The tendency is to be well-schooled in our folk music and not in our classical music,” says Anagnost. “But don’t forget that Theodorakis has also written an opera and has written for the ballet. We did his Third Symphony as an American premiere and he called me and he was thrilled. He said, ‘I wish we had more Greeks out there doing the symphonic stuff.’”

In fact, there are: Anagnost says during his first year at Juilliard he was the only Greek, but now there are several promising performers in piano and opera.

He himself began taking lessons at six in Manchester, New Hampshire when his parents bought a piano (“My grandmother had a piano, and my parents say as a little boy I used to sit at the piano and just bang.”) He got waylaid by baseball at nine, but when his parents threatened to get rid of the piano he went back to it at 13, added cello at 17, clarinet at 19, and voice at 20.

“I wanted to sing,” he admits.

But while at Juilliard, he heard the Little Orchestra Society needed a choral director, “because there was a Greek chorus, and I trained the Greek chorus at Juilliard, and then they kept me on,” he remembers.

He went from choral director, to assistant conductor, to associate conductor, then finally music director.

“I wanted to conduct,” he says. “I really wanted to conduct, and that’s where I put all my efforts.”

His concert schedule now lasts from September to June, and there’s been talk of a concert in Greece, at the Megaron in Athens.

“It’s difficult to get away because of our different series,” he says. “We’re really working all the time. But I would love to go over and do some work. We’ve been invited, but I just haven’t had the time to do it.”

He does visit Greece often (his parents are from Macedonia) during his infrequent breaks and his summers off, and he’s been “all over Greece, as a tourist.”

“I’m American-born but when you go back, you just feel it’s your roots,” he explains. “There’s an energy that I get from going back there, a wonderful energy. It’s just a wonderful country.”