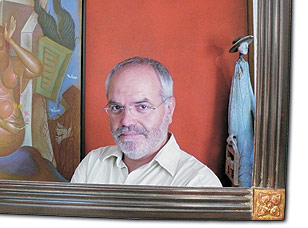

Those who think of Byzantine painting as an archaic art form—stuck somewhere between the confines of art history books and holy structures—should take notice. Byzantine painting, the sacred expression of the Orthodox Church, is making a comeback. At the forefront of this revival is a painter whose work bridges the old with the new. George Kordis, a Greek-born artist, is reintroducing this mystical painting tradition, enriching it with western techniques and making it accessible to art lovers around the world.

Throughout his impressive career, Kordis has specialized in the theology and aesthetics of Byzantine painting. Both secular and religious works comprise his sizeable contribution to Modern Greek art. His paintings blend tradition with the ideals of modernism and his “personal mythology”—how he experiences the world. As an iconographer and teacher of icon painting at the University of Athens and Yale University’s Institute of Sacred Music, he’s heralding a return to this ancient art form. Whether making a creative painting or an icon, he uses the same time-honored techniques handed down by Byzantine craftsmen.

Kordis was a theology student at the University of Athens when his professor, Father Symeon Symeou, a well-respected Cypriot iconographer, encouraged him to take up icon painting. Several years later, while studying painting technique at The School of Fine Arts at The Museum of Boston, he had the idea to expand his artistic skills beyond iconography. He began studying Byzantine painting as a system of forms. In this classic art form, he saw a series of interconnecting relationships—a way to “express the contemporary man with his needs and concerns.” Realizing its functional value, he expanded the scope of his work to secular painting.

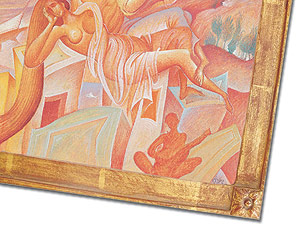

Separation, isolation and autonomy are some of the themes that his work addresses. Creating a bond with the observer is the ultimate objective of the Byzantine painter. To achieve this effect, Kordis mixes and repositions the different painting elements, for instance through drawing lines and the use of color, to establish balance and movement. This technique gives his paintings lifelike qualities, such as motion, rhythm and unity. Figures follow the observer’s movements and become part of the present life of the beholder. The painting grounds the observer in reality instead of cultivating the illusion of separation. Its energy is absorbed and felt by the senses, reflecting an image of the world in a state of harmony.

The effect is mystical—flat figures with large eyes that appear weightless—as if they’re floating on air. After all in Byzantine art, the idea is to depict the soul rather than the body. Natural forms are exaggerated or diminished depending upon the inner qualities the painter wishes to express. It’s easy to see the heavenly images and qualities of the spiritual world expressed in Kordis’ paintings. A sense of serenity and peace contributes to a transcendental experience, reminding observers of a reality beyond themselves—somewhere deeper than the eye can see. A master craftsman, Kordis uses his paintbrush like an alchemist, blending the symbolic language of Byzantine art with a keen aesthetic eye to evoke an inner silence that, in the words of Saint Paul, "leads to truth."

Byzantine structure, according to Kordis, is a framework in which to “unify the broken image of the world.” It’s a medium devoted to uncovering the essence of life—in its purest and simplest state—through love. In his view, love is the unifying force in life. “It’s the way things come together and communicate in order to create unity,” he says. But, he warns that an artist’s skill level is only part of the equation. The artist must have a spiritual bent in which to connect to the “ethos” that lies at the heart of this art form. And so it’s the task of the Byzantine painter to seek and find the soul in the painting—the hidden element that bridges the worlds of separateness and existence—where “isolation becomes love.”

In the end, love is the underlying element in all of Kordis’ work and he draws inspiration from popular Greek writers and poets whose works embrace the subject, such as Kontoglou, Karkavitsas and Elytis. By adapting timeless themes into a visual language, he is reintroducing unforgettable characters and literary works in a fresh light. Though his subjects provide a platform for him to express the face of his country and to explore themes that are embedded deep in the psyche of many Greeks, their universal appeal is undeniable.

A selection of Kordis’ secular work depicting adventures in love will be on display at Yale University in New Haven, CT, from October 11 to October 25 at the Henry R. Luce Hall, 34 Hillhouse Avenue. The series of paintings features a combination of 20 egg tempera paintings and 10 pencil drawings—some of which were inspired by the work of the author Alexandros Papadiamantis and the poetry of George Seferis.

Visit http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/hsp/# for more details.