|

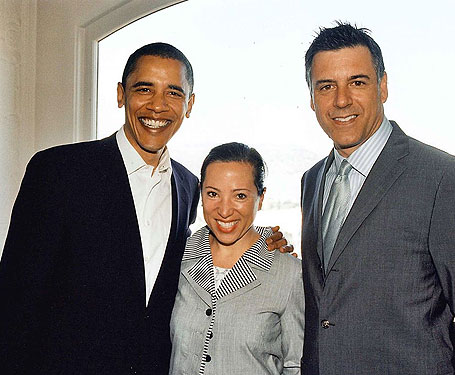

He is one of the most thoughtful journalists of our time, a globetrotting foreign correspondent with articles in Newsweek, The Los Angeles Times, The San Francisco Chronicle and The Wall Street Journal. And some of us know him as the “white knight” who rescued The Washington Monthly and is now the venerable magazine’s president and publisher. He and Peter Laufer also do the “Washington Monthly on the Radio” program. Together they recently wrote Hope Is A Tattered Flag: Voices of Reason and Change for the Post-Bush Era and NEO spoke with Kounalakis shortly after the presidential election.

by Kaymaria Daskarolis

NEO: What inspired you and Peter Laufer to write Hope Is a Tattered Flag? You already had the conversations in your radio program, “Washington Monthly on the Radio” – why collect and publish them in a book?

KOUNALAKIS: What we had found in the course of our doing the radio program is that there was an incredible sense of optimism and hope around the country, even during the darkest days of the Bush administration. We saw that despite the failures and the travesties of some of the policies pursued by the Bush administration, the majority of Americans, and certainly a great number of those with whom we spoke on the radio program, were still trying to move on and figure out solutions that were inclusive and broad-ranging and global. You get one audience from your radio program – a fairly large audience – but we thought we could reach a different audience and a broader audience by taking some of those interviews and editing them into a concise and interesting read for a broader public.

NEO: What did you think the value would be of a broader or different audience having access to these conversations, and what do you believe is the value in general of having these conversations made available to the public, whether on the radio or in a book?

KOUNALAKIS: I think there is value in sharing the types of insights and personalities that make up our country, and to share those at a time when the voices that seem to be coming across are very limited and not as broad-based as some of the ones we have. Within the pages of our book, we have lots of newsmakers and people with whom we are familiar, but even with those people we try to get to things about them or their perspectives that are not typical. Many of us know who Joe Klein is – a reporter who is also a successful novelist and an analyst of the political scene – but he gets personal within the pages because we push him in very gentle ways and we get him to a point where he’s actually talking about personal experience. That changes the way that we then perceive him and how he comes to the type of analysis that he does. And that’s true for almost everyone we talk to. I think Pat Buchanan is an exception because there’s no way you can get into that soul, but for most other people who are in the book it seems like you can get in a little bit further and a little deeper than the sort of sound bite world that we’re used to with those who make the headlines and who are newsmakers. We also bring into the book a number of people to whom you don’t have access on a daily basis and whom maybe you don’t come across. They include the Black Elk from West Virginia, a guy who is trying to legalize ferrets as pets in California, and a number of idiosyncratic and iconoclastic individuals.

“There’s never been anything like this moment. What this represents has never occurred in the past.”

NEO: I had that experience while reading some of the conversations in your book. I felt like I was getting an opportunity to know these people who are forming and shaping pop culture and governmental policy – some of the greatest minds we know to exist on the planet today sharing more personal insights. It was very interesting to read.

KOUNALAKIS: That was our goal: to humanize these individuals whom we know, but also to provide us with an insight into their thinking, their hopes – and for those who had a means of presenting the picture of what America should look like, their voices of reason.

NEO: And so joining your voice to their voices of reason, what do you think we – both as Americans and as citizens of the world – should be demanding of ourselves right now? What should we be holding ourselves accountable to both privately – in our homes, with our families – and publicly, in terms of our civic responsibilities?

KOUNALAKIS: First of all, I now have the privilege of having this interview with you well after the book was published, because we went to press prior to our election in November – a few months prior to that election is when the book came out. We’ve fulfilled one part of our responsibility as citizens by showing up to the polling booth in large numbers. A big part of our civic responsibility is something as simple as going out and voting. I think with the response to this election cycle in the voting booth, all of us have taken a much larger responsibility for those institutions and individuals who represent us. So it starts at a very basic level, but an important one nonetheless. Regardless of how we would have voted – we have in hindsight the ability to say that it was for Barack Obama – but in either case we would have elected a course of change from our last eight years. Now, while we talk about civic engagement, responsibility, and participation in our democratic United States of America, there’s also something uniquely Greek or Greek American to this in that I think we – and I’m including you and those who read NEO Magazine in this – see ourselves to a greater or lesser degree as stewards of that democratic tradition. It’s partly an accident of birth and geography, and a continuation of cultural tradition, but whatever those reasons are we are burdened with the honor of upholding a democratic tradition and promoting it culturally, socially, and politically. And so, I think we have a higher responsibility towards activism within the political realm. I think we have a higher burden towards leading our communities in the business world and in other areas, and doing it in a visible way that actually sets an example, to the degree that it’s possible. I think you can point to any realm of our academic or social or cultural life and see that we oftentimes, as a community, despite our small numbers in this country, are overrepresented. So I would just say that I hope to pass that on – and I do both through the radio program and in a minor way through the book – to our larger community, to the community that surrounds us, and of which we are actively a part.

NEO: Do you see any values that are upheld and really important to the Greek American community that you think would make a huge difference if they were more culturally and authoritatively embraced today?

KOUNALAKIS: I think what you’ve seen during Obama’s campaign is that there is an embracing of those very deep basic values that we uphold and represent. He talked during the entire campaign in a collective voice, he always spoke about us, he seldom used the personal pronoun I. That is very much an ancient and democratic value – the power of a collective wisdom versus the individual tyrant, whom we’ve experienced recently – who thought that he could with a very small cabal make decisions, without taking into account the majority of the nation. It doesn’t mean that you’re bound to decisions or the collective tyranny of the majority – that’s why we elect leaders, to be wise and to make decisions on our behalf, but to be disregarding of those voices and of that majority in the way this Bush administration has been is unprecedented in my lifetime. I am very optimistic in what I’ve seen so far in terms of our values being represented, whether they be our values of faith or our values of governance, and I think that’s why Obama won the majority of votes, he really was able to strike that chord. Now we need to see, under the pressures of governing a very complex system, whether those can be applied and implemented. KOUNALAKIS: I think what you’ve seen during Obama’s campaign is that there is an embracing of those very deep basic values that we uphold and represent. He talked during the entire campaign in a collective voice, he always spoke about us, he seldom used the personal pronoun I. That is very much an ancient and democratic value – the power of a collective wisdom versus the individual tyrant, whom we’ve experienced recently – who thought that he could with a very small cabal make decisions, without taking into account the majority of the nation. It doesn’t mean that you’re bound to decisions or the collective tyranny of the majority – that’s why we elect leaders, to be wise and to make decisions on our behalf, but to be disregarding of those voices and of that majority in the way this Bush administration has been is unprecedented in my lifetime. I am very optimistic in what I’ve seen so far in terms of our values being represented, whether they be our values of faith or our values of governance, and I think that’s why Obama won the majority of votes, he really was able to strike that chord. Now we need to see, under the pressures of governing a very complex system, whether those can be applied and implemented.

“I don’t think we’ve ever in our history as a nation been able to as symbolically break with an historical injustice as we have now.”

NEO: This is a very important and historic time for us.

KOUNALAKIS: There’s never been anything like this moment. What this represents has never occurred in the past.

NEO: Some people have been drawing comparisons between what’s happening today in our country and what was happening when FDR was in office. Do you feel those parallels can be drawn?

KOUNALAKIS: When we talk about FDR, often the question is focused on economics and whether or not we are looking towards a period of greater involvement of government within our economic life. Even during the Bush administration, we’ve seen this occur. I don’t think it’s a question of whether or not our new president takes us in those new, more interventionist directions. Our current administration has taken us there. And that’s been in response, by the way, to a crisis of their making, for the most part – or at least it’s been exacerbated during the Bush administration. So there’s a certain level of reactivity that you have to deal with on the economic front. I think really the question is, has there been such a break with the past in any other previous administration? And I can honestly say that I don’t think we’ve ever in our history as a nation been able to as symbolically break with an historical injustice as we have now. It is equivalent to and as dramatic as the greatest things that have happened collectively in this nation. I think it’s far beyond any previous election, and the United States has propelled itself into a new world and is now in the process of reinventing itself as a result of its democratic behavior. Of course because of that, collectively our expectations are very high – the world’s expectations are very high – and that will probably be one of the greater challenges, because any administration is limited in the amount of work that it can do. But symbolically it is an unprecedented change.

NEO: And what are your hopes and expectations for the Obama-Biden administration?

KOUNALAKIS: Well, they are charged with two things. One is cleaning up the mess and the messes of the last eight years. The question of the war and peace, of course, in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as the broader spread of extremist violence. Secondly is the economy. In a time when we are beyond any immediate solution being available to us, they have now got to reinvent government intervention, regulation, and our capitalist system, starting with the fundamentals of banking and moving into manufacturing. These challenges are of course beyond any individual and are going to prove very challenging to any administration. Those are just the things they have to fix. They don’t include the changes they want to make to make it a more equitable society where we can move away from these large disparities of wealth and poverty, where we can guarantee health care for our people. The challenges are massive. Barack Obama said from the very beginning, recognize the challenges and recognize that I am only a human being, I am fallible, and I will make mistakes; recognize within yourselves that in order for us to achieve anything, to be successful in solving any of these problems, I must request both sacrifice and service from you as a people, from us. So the question is, are we up to it? The way that we framed our book and the way we frame our radio program is to say that yes, we’re up to it, we just have to be asked. And we need leaders who have that level of vision and articulation to be able to inspire us to service, to make sacrifices.

“The United States has propelled itself into a new world and is now in the process of reinventing itself as a result of its democratic behavior.”

NEO: What do you think sacrifice and service look like for the average American?

KOUNALAKIS: What sacrifice does not look like is plopping down your credit card and becoming a consumer rather than a citizen. What it looks like for any individual is different, but I think in general one of the sacrifices is a sacrifice of material wealth to the point where we have to agree to be able to levy on ourselves the ability to pay for services that we deem are necessary. We have to pay for education, we have to pay for health care. Obama said he’s going to levy higher taxes on those who make more than a quarter of a million dollars per year, so we’ll have a more equitable tax system where the wealthier pay a larger percentage of their income. And service again is very individualized. For some people it means going into the military and serving in our armed forces, protecting and defending democracy – not promoting democracy at the gun of a point, but certainly defending it both here and abroad. For others it’s community service and for others it’s teaching kids to read or helping older people. It is a highly individualized action, but one that can be facilitated by our local, state, and federal institutions, and certainly catalyzed by a leader who deems it important and has walked the walk. George Bush certainly never had the moral authority, when you look back at his history. Not to say that someone who is young and reckless is unable to take on a mature role later in life, but he certainly doesn’t have an inspiring personal story or narrative to point to when he asks of us certain things, or for sacrifice or service. I think you start at a much higher point when you’ve done it yourself.

“You need everyone to come up with a collective wisdom and solution to our problems.”

NEO: In your conversation with the founder of Washington Monthly, Charles Peters, you said that as a journalist starting out you kind of went by the credo, “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” Do you still operate by that? Did you seek to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable in your book, Hope Is a Tattered Flag?

KOUNALAKIS: It’s interesting you should ask. I’ve been thinking about that lately. I think that one of the other things that has occurred with the election of Obama is that that credo and that attitude is divisive, and I’m not sure that I hold to it any longer. It implies that you’re doing something to a group of people whom you deem as unworthy of something, so I have to say that I really am revising my attitude towards that. Certainly comforting the afflicted is important in journalism, but afflicting the comfortable is not really appropriate. I think challenging the comfortable in ways that are positive is appropriate – challenging them to try to do better, to also participate in sacrifice and service; holding them to the high moral standards that we expect from our civic leaders, those who hold a great deal of wealth and who have power. So I guess I would change it now to challenge the comfortable. And some might say that maybe it’s because I personally am in a very comfortable position these days, but I don’t think so. I think it has more to do with the bi-partisan, inclusive decision that we’ve made in this election that say you need everyone to come up with a collective wisdom and solution to our problems.

|