by Dimitri C. Michalakis

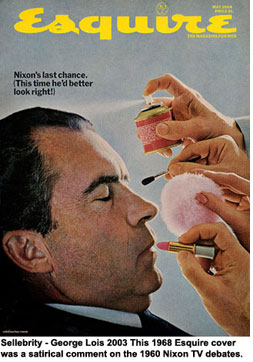

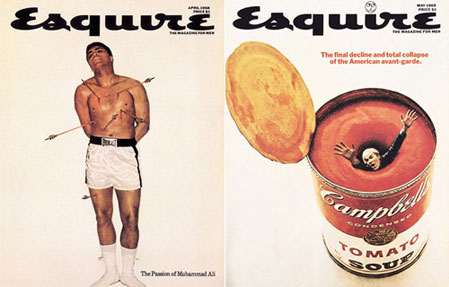

“Dubbed "The Superman of Madison Avenue" and "The Golden Greek", George Lois grabbed the advertising industry by the throat and revolutionized the game with campaigns that were always startling and never dull: the minimalist Volkswagen ads, the Braniff "When you got it, flaunt it" slogan, Mickey Mantle blubbering "I want my Maypo" and a reprise with "I want my MTV!", among others. He also worked on Robert Kennedy's 1964 senatorial campaign, fought to free Rubin "Hurricane" Carter and designed ten years of covers for Esquire magazine that encapsulated the decade. "George Lois may be nearly as great a genius of mass communication as he acclaims himself to be," declared New York Magazine.

“Dubbed "The Superman of Madison Avenue" and "The Golden Greek", George Lois grabbed the advertising industry by the throat and revolutionized the game with campaigns that were always startling and never dull: the minimalist Volkswagen ads, the Braniff "When you got it, flaunt it" slogan, Mickey Mantle blubbering "I want my Maypo" and a reprise with "I want my MTV!", among others. He also worked on Robert Kennedy's 1964 senatorial campaign, fought to free Rubin "Hurricane" Carter and designed ten years of covers for Esquire magazine that encapsulated the decade. "George Lois may be nearly as great a genius of mass communication as he acclaims himself to be," declared New York Magazine.

Did you once say, "If advertising is a science, then I'm a girl"?

That was my facetious and maybe crude way of saying that advertising certainly was not a science, but was an art...Advertising is an art based on some basic understanding and knowledge of marketing. But to turn that understanding and marketing into exciting strategy, and exciting execution, and advertising that knocks you down and convinces you to do something, is so far from being measurable and so far from being a science, it isn't funny.

Your work has a "commando flair for the audacious" said The Wall Street Journal. Do you try to outrage the industry?

It was just a natural thing, I didn't think it through...They still call me a wild Greek. And that kind of reputation never bothered me. In fact, I always got a kick out of it. I talk like I'm from the Bronx, and I kind of lay it on a bit thick. I don't care. I think from the beginning I was considered the enfante terrible of Madison Avenue, Madison Avenue's bad boy...I still have the same craziness and excitement about what I do and I still have a temper when I protect my work...Most guys say, "Jesus Christ, George, how old are you now? You're sixty-six. When are you going to stop?" I say, "I don't know." I think my passion, the passion for what I do, if anything, grows.

What did you want to contribute to advertising?

I always understood, I almost created, the idea of creating ideas. Of creating what I wall The Big Idea. I always look for the startling, surprising idea...Advertising should attack your throat, your eyes should tear, you should choke up, you should almost pass out. When you see an advertising idea, it should absolutely be a blow to your stomach.

Were there risks being audacious in what is really a very conservative business?

Oh, sure, and by the way, you do take wounds. Because with all the great excitement, all the great things you do, there have been dozens and dozens of rejections of work that I thought was brilliant. But, somehow, I liked the excitement of putting an idea down on a flat piece of paper and creating a commercial that changed people's minds about something.

Why did you leave agencies you started and were very successful?

My gag was, "Hey, I'm going to keep doing it until I get it right." I started my last agency, I think in 1976-1977, so it's almost twenty years now. And I think really what happened in the first agency was that I was one of three partners. The second agency, I brought two young guys with me and made them equal partners. And I think the third time I said, "I'm not going to do this again." I mean, it's really as simple as that. I said, "This time I'm going to run it and I don't want to argue with anybody."

You also mistrust success?

What I told everybody was, "I'm too young to die." What happened, basically, was all my partners, everybody around me, were incredibly successful and they all started to chicken out and started to say, "Now that we're big and successful, we gotta quiet our work down." And I remained the young Greek, or young Turk, raising hell. And I remember I was 35 and everybody around me was 45 and they were all acting like they were dead, or gonna retire. And I surprised the hell out of them. I just left to start another agency. I shocked the advertising world.

Why did you do the Esquire covers? To express yourself?

No, I can express myself in a million ways in advertising. No, what actually happened in 1960-1961--Harold Hayes was the editor, and a great editor, and I think he was doing a great magazine--but nobody recognized it was a great magazine. And he came to me and he said, "George, can I just have your opinion? I know you're a hot-shot art director. Do you have any suggestion how I can improve the covers?" I said, "Oh, God, I mean, how do you do that?" Well, everybody talks about what we should do...bah-bah-boo-bah-bah. And I said, "Well, that's ridiculous. Is that the way you do your articles?...I'll do one for you." And I did one, and it became very famous [Floyd Patterson, the seven-to-one favorite in a fight with Sonny Liston, shown knocked out in the ring]. The balls of calling a fight on the cover of a men's magazine. And then I just kept doing them, and the only reason I kept doing them is I told Hayes, "I'll keep doing them as long as you give me what's going to be in the magazine and I'll deliver your cover. And you gotta run it. The first time you say you don't want that cover, you won't run it, that's the end of that."

No, I can express myself in a million ways in advertising. No, what actually happened in 1960-1961--Harold Hayes was the editor, and a great editor, and I think he was doing a great magazine--but nobody recognized it was a great magazine. And he came to me and he said, "George, can I just have your opinion? I know you're a hot-shot art director. Do you have any suggestion how I can improve the covers?" I said, "Oh, God, I mean, how do you do that?" Well, everybody talks about what we should do...bah-bah-boo-bah-bah. And I said, "Well, that's ridiculous. Is that the way you do your articles?...I'll do one for you." And I did one, and it became very famous [Floyd Patterson, the seven-to-one favorite in a fight with Sonny Liston, shown knocked out in the ring]. The balls of calling a fight on the cover of a men's magazine. And then I just kept doing them, and the only reason I kept doing them is I told Hayes, "I'll keep doing them as long as you give me what's going to be in the magazine and I'll deliver your cover. And you gotta run it. The first time you say you don't want that cover, you won't run it, that's the end of that."

You showed Muhammad Ali as a martyred St. Sebastian for refusing the draft but portrayed an ordinary kid as a draft dodger: What's the difference?

Ali stood for his principles, as he said, it was a terrible war. It was a war of genocide, I don't think he used those words. I'm a Korean veteran, I fought in the Korean War, I thought that was a war of genocide, I thought that was an awful war, and I think the Vietnam War was a continuation of that attitude and that war. So [Ali] made a principled stand...But then there were guys who were pure draft dodgers, draft dodgers like the Clintons of the world and half the guys you ever heard of, who did everything they could to not fight in the war. And to me, there's a moral difference between them.

Ali stood for his principles, as he said, it was a terrible war. It was a war of genocide, I don't think he used those words. I'm a Korean veteran, I fought in the Korean War, I thought that was a war of genocide, I thought that was an awful war, and I think the Vietnam War was a continuation of that attitude and that war. So [Ali] made a principled stand...But then there were guys who were pure draft dodgers, draft dodgers like the Clintons of the world and half the guys you ever heard of, who did everything they could to not fight in the war. And to me, there's a moral difference between them.

You worked for many causes, including the freeing of boxer and convicted murderer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter.

I guess I'm a compassionate Greek, or is that redundant?...I like to think I stand up for truth and justice and the American way. I mean, I don't like when people get pushed around. I don't like the Nazi bastards, I'm like Jackie Mason. And I've always been involved politically. I did Bobby Kennedy's ad campaign. And I guess I feel strongly about certain things, and I'll do all I can to make things right. That doesn't mean I'm right, but at least I think I am.

Why did you title your 1972 autobiography "George Be Careful"?

Giorgo, prosexe. From the day I was born my mother told me, "Giorgo, prosexe." Certainly as far as my work is concerned, you can't be careful, you have to be dramatic, you gotta be exciting, you gotta be on the edge.

Do you think you changed the world, as you advised others to do?

Well, I mean, it's a crazy thing to say, except every time you attack a problem you gotta think that way. For good or bad, there's a lot of things I did that I know changed the world, as far as advertising is concerned. I think I influenced hundreds, thousands of people in the business...And there's a lot of things that wouldn't exist without me today, that literally changed the culture, for good or for bad: like the MTV's, the USA Today's, and the Tommy Hilfiger's, and the Lean Cuisine's, and a lot of things. Bobby Kennedy absolutely would not have won his first election in New York State, that's for sure...So it's a grandiose way of talking when you say you can change the world. But what I'm basically trying to teach people and young people, is that communications--dramatic, bold, edgy--can literally sell ideas. And the idea could be selling a product, something as mundane as a product, but important to you and important to your client, or selling the idea of justice.

Can you get as excited over selling frozen food as electing Bobby Kennedy?

I really enjoy that difference. The really silly thing about it is, I can get excited about selling almost something so mundane. I say, "How can you get so excited, George?" I think that's the excitement that when you work on something, you make that a thrilling part of your life. From selling a restaurant...to doing Esquire covers...I don't think everything should be important. But the point is, everything I work on is important from the point of view of making it successful, because I work in commerce and people come to me and they have a product, and I gotta make that thing goddamn sell. No matter what, I'm gonna make it work and I know the only way to truly make it work is to come up with an idea that startles the hell out of you...

I really enjoy that difference. The really silly thing about it is, I can get excited about selling almost something so mundane. I say, "How can you get so excited, George?" I think that's the excitement that when you work on something, you make that a thrilling part of your life. From selling a restaurant...to doing Esquire covers...I don't think everything should be important. But the point is, everything I work on is important from the point of view of making it successful, because I work in commerce and people come to me and they have a product, and I gotta make that thing goddamn sell. No matter what, I'm gonna make it work and I know the only way to truly make it work is to come up with an idea that startles the hell out of you...

What keeps you motivated?

I say if you don't get burned out every day, you're a bum. When you go home at night, you should be exhausted, I mean, mentally and physically exhausted. And then you get up in the morning and you come to work and you say, "I'm going to kick ass today." And then by the end of the day you can't even see straight. And maybe a lot of it is my upbringing, it's in my blood. My father worked 20 hours a day, my mother worked 22 hours a day. It's almost a guilt thing, it's also growing up in the Depression. I mean work, work, work. Don't waste your time.

Did your parents understand your career?

No, they didn't have a clue. My father [a Bronx florist], one morning, he came to wake me up to go to the flower market...and he said, "Giorgo, get up. It's four o'clock in the morning." I said, "Dad, I'm starting college today." "What college?" "I'm going to Pratt." And he said, "Okay." That was that. And he thought I would take over the store and I just went to school. And I think he thought I was nuts, he was very worried about me obviously...Then I start an ad agency and my father comes to the agency. He's looking around, and you try to explain it, and he was a pretty sophisticated guy, but it was a little mind-boggling. What he taught me, and what I got from my parents, is that you work your ass off and do everything right. Do everything right. Just do everything perfectly. I still come in at 5:30 in the morning and first thing I do is clean the kitchen and I make the coffee. And my wife five o'clock in the morning bakes stuff I bring in with me. She's a Polish girl who has Greek instincts: I get up, she gets up.

Any regrets?

I don't think so...I remember there was an Aspen conference ten years ago and they asked me to be a speaker...And they had this big intellectual thing about how you can take advantage of learning from your mistakes. And at the every end of the whole goddamn thing, with these impressive people, the intelligentsia of the world there, I got up and I said, "I never made a mistake in my life. The second I make it, I forget about it. It doesn't teach me a goddamn thing." ...Man, I forget about it. I didn't make the goddamn mistake. Kick ass the next day.