By Katerina Georgiou

This setting is a far cry from the streets of Harlem where he was born and raised. And like the heroes in the stories he tells, Grosso is an ordinary guy living an extraordinary life. The kind that would make a great film—that is, if it hadn’t already inspired one.

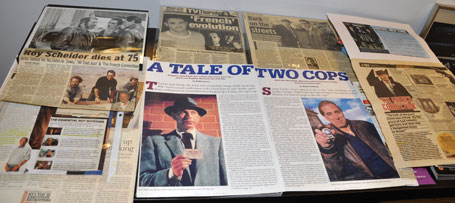

Not just any film, but a five-time Academy Award winning one—“The French Connection.” The book and film were based on his real life experience in the celebrated crime bust as an undercover detective along with his partner of sixteen years, Eddie Egan, who was known as “Popeye Doyle” in the film.

In addition to launching his film career, it led to his becoming the youngest first grade detective in the history of the NYPD, accomplishing in three years what it normally takes decades to achieve.

“I didn’t do anything alone,” he said. “I got a lot of help from the people I worked with.”

Upon entering his office, Grosso removes his Colt 38 revolver from its faded holster. It’s the same gun used by Al Pacino in the legendary film, “The Godfather” on which Grosso served as technical consultant and actor. The gun is a collector’s item but he has no interest in selling it. He plans to donate it to the New York City Police Museum instead.

With the success of “The French Connection,” Grosso became a much sought after technical advisor and story consultant on numerous films and television shows, including “Kojak.” He also helped produce the first twenty-two episodes of that series as well as the program, “Baretta.”

Since co-founding Grosso Jacobson Productions in 1980, he has overseen more than $400 million in productions.

“I just hit a stroke of luck,” he said of his many accomplishments.

It’s a curious choice of words given that storytellers leave nothing to chance. But, as one expects from a self-reflective man like Grosso, this comment is followed by an explanation—a personal one that he seldom shares.

“I always thought that the good things that happened to me…that was God’s way of giving back for taking my father,” he said of his untimely death when the younger Grosso was only fourteen.

“If you want to believe in God—and I do—then you’ve got to believe that’s what he does.”

Though his father’s presence was brief, he provided him with the guiding principle that shaped his life’s perspective.

He recalls one afternoon his father caught him speaking with some neighborhood kids selling stolen items and pulled him aside for a swift lesson.

“He said: ‘you see that record player…you know the one in your grandmother’s house?” said Grosso, mimicking his father’s stern voice. “When you buy these things that’s where they come from…houses like hers. He looked me in the eye, grabbed my chin and said: ‘Do the right thing.’ Then he turned and walked away.”

Before the loss of his father, Grosso lived a carefree existence revolving around sports and Sunday dinners with his large extended Italian-American family—all living within arm’s length of each other. His early years offered a glimpse of promise: he skipped two grades in school, was an athlete and talented artist.

But his sense of direction was eclipsed by grief. He temporarily dropped out of school and took a series of odd jobs. His homemaker mother, a widow at thirty-three, was left to care for him and his three younger sisters.

“She made a lot of sacrifices and never married again,” he said.

A chance opportunity to escape a mundane existence came when his impressive cartoons caught the attention of New Yorker magazine. They published his work, and he soon found himself crossing paths with such luminary artists as Al Capp.

Being a cartoonist eventually led to disillusionment as he found little creativity in the “assembly-line” process of working for a publication. The low pay was a further disincentive, and he couldn’t justify making a career of it.

Returning to his old neighborhood after serving in the army, his life took a fateful twist during a routine game of basketball with friends. A pal from the neighborhood going downtown to pick up applications for what he mistakenly thought was the fire department offered to bring some back for the others.

The applications turned out to be for the police department instead, and after applying on a whim, Grosso was accepted. His neighbor wasn’t so fortunate.

“The six of us in the park were too lazy to go downtown...he goes all the way down there and doesn’t make it,” Sonny smiled wryly.

As a cop he was assigned to his old neighborhood in Harlem—an experience that taught him that the truth was multi-sided. Now he had the chance to observe it from the other end—this time as the “guy in blue.”

“It was difficult for me to decide what to do in the given instance,” he said. “You’d walk into an ice cream parlor—a place full of young guys—and you were a young guy yourself. I was trying to remember how I felt as a kid, and how I should feel now understanding that.”

Unbeknownst to him at the time, developing empathy on the job and conducting countless Q&A’s would serve him well later on as a producer by giving him a deeper understanding of character motivation and a sharp ear for dialogue.

These qualities add a level of authenticity to his productions and keep him focused on his purpose of uncovering the human condition through entertainment.

Among the projects he's developing is a musical on the life of the American tenor and movie star, Mario Lanza, and he’s in talks with Greek singing sensation, Mario Frangoulis, to star.

He's also working on a biopic about the Greek-born former Jimmy Weston’s supper club host, Dino Pavlou, and his lifelong friendship with Frank Sinatra.

Pavlou’s compelling story is about his daring escape from the hands of Communist guerillas in Greece and his piercing of the exclusive New York supper club scene where he became a trusted member of Sinatra’s inner circle.

“When he was growing up as a kid I don’t think Dino ever thought I’m going to be maitre d’ at one of the most famous clubs in New York and mix with Presidents and Frank Sinatra. There aren’t ten guys in this whole country that have that ability.”

And there probably aren’t many producers like Grosso—who worked on two films with Sinatra and also considered him a close friend—that can personally relate to the unusual friendship between an ordinary guy and an American icon.

“As you get older what you really have left are your memories so you should make them as good as you can,” he said.

“But experiences don’t make you understand everything. There are still a lot of mysteries in life that most of us call luck.”

And that makes you wonder if so-called luck is simply a meaningful choice in disguise that we make with a little help from above.