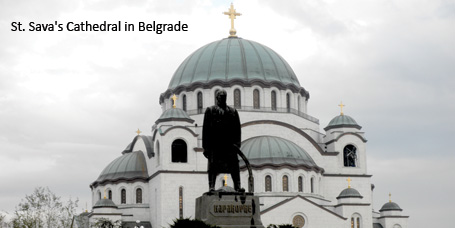

Now that we are in the midst of Great Lent, it makes sense to consider borderless Orthodoxy. Here in Serbia, where we currently live, Orthodoxy is the religion of the vast majority of the population, so much that the saying “to be Greek is to be Orthodox” could apply to Serbs as well.

At this time, the churches fill, Lenten foods start to appear on supermarket shelves, and fish stores do a bigger business as the Serbs, about as meat eating a nation as any on the planet, curtail their consumption.

Serbian Orthodox are about as observant as their brethren in Greece, though the years of Tito’s soft communism, together with the multi-ethnicity of the former Yugoslavia (and certain parts of Serbia) result in far less Church involvement in society. Unlike in Greece, there is a strict separation of Church and State. Civil documentation and government offices have no mention of religion, though my son, in first grade, takes Orthodox Catechism as part of the curriculum. I thought of my service in the Greek Army, with mandatory liturgies and the Lord’s Prayer en masse before meals. None of that here. While Serbian Churches are well-attended and adorned, the tiny chapels that are ubiquitous in Greece are far less common.

Though the Church is separate from the State, and most Serbs seem to favor this, the trappings of Orthodoxy abound. Prayer bead bracelets (komboskinia) or rear view mirror crosses are everywhere and it most houses have an icon alcove, usually of the household saint. This requires some explaining. Serbs, unique among Orthodox peoples, do not celebrate name days but rather the saint’s day of their household saint, known in Serbian as the “Slava.” Household saint days are the most important days for Serbians except for Easter and Christmas, and even non-religious Serbs tend to hold this tradition dear. Household saint days pass from father to son, but the eldest male (father or brother) will usually host the Slava, to which family, koumbaroi, and guests visit. Generally, kolyva in a cross pattern is provided upon entry to the house, one crosses oneself, eats the koliva and proceeds to drinking and eating.

Of course, the saint’s days dates are different from the Greek Orthodox Church, as the Serbians have kept the Old Calendar, which is 13 days later than the New Calendar. This results in Christmas being on January 7, but Easter is always the same day for all Orthodox. Most Orthodox or Eastern Christian Churches retain the Old Calendar, but the Greek, Bulgarian, and Romanian Orthodox have opted for the New Calendar.

Aside from the language of the Church, which is Old Church Slavonic, Orthodoxy is celebrated in the same way. Like in Greece, and in contrast to America, people will often mill around during the liturgy, as there are no pews, or step outside. To a degree, again like in Greece, the Church is a reference point for the Serbian national identity in the face of all the country has gone through in the face of Yugoslavia’s dissolution. It thus receives a great deal of nominal respect even from completely non-religious Serbs.

The religious atmosphere also varies by region. Southern Serbia is solidly Orthodox, except for a few enclaves of Albanian or Bosnian Muslims, and Churches are in a Serbo-Byzantine style easily recognizable to a Greek. The situation is different in Vojvodina, Serbia’s northern province, where we live. In Vojvodina, which experienced only a century and a half of Turkish rule but was under Austro-Hungarian rule for two centuries until 1918, the atmosphere and architecture recall Vienna and Budapest. Most Vojvodina Orthodox Churches, such as the one we attend in Sombor, are in a baroque style nearly identical to Roman Catholic Churches—on the exterior. The Orthodox Churches have a different orientation to the Roman Catholic ones, and the interior, with narthex and iconostasis, is totally different, though in Vojvodina the iconostasis is likely to have frescoes clearly showing Renaissance and Baroque schools. When I mentioned this to a Serbian priest in Sremski Karlovci, a beautiful Vojvodina town that had been the seat of the Serbian Patriarchate for two centuries, the priest said, “well, the Renaissance owes itself to Byzantium, so these traditions are simply returning to us.”

Vojvodina has over two-dozen nationalities; Serbs, while a small majority, live side-by-side (or in marriage) with Hungarians, Slovakians, Romanians, Croatians, Carpatho-Russians, and a score of other nations, including small pockets of Greeks from the Civil War era. Orthodoxy coexists here with Roman Catholicism and a few Protestants, in the same towns, and often in the same household. This often results either in a hybridization of celebrations, or a strict division of traditions, but in a general atmosphere of tolerance. This makes Vojvodina probably the most ethnically diverse part of Europe, and while religion serves as a mark of identity, most people, particularly in Sombor, celebrate inclusively. As one Sombor journalist, a Serb married to a Hungarian, told me, “the worst insult to call a Somboretz (Sombor citizen) is that he is intolerant.”

Holy Week and the Easter celebrations are to a great degree similar to those in Greece, which is not surprising given the common religion and Byzantine culture, but climate and cuisine do have some variations. The variations and difference increase the further north in the country. Post-Anastasi magiritsa is not common here, and while lamb is the preferred Easter meat, in Serbia pork is also ubiquitous. Again, mountainous southern Serbia is more likely to have lamb than further north, and in the south oven baking and spit roasting is more common than in the north, where stews and cooked meals are the norm, including for Easter. Oil, whether during the fast or the feast, is usually sunflower oil, a function of cost and climate, rather than the ever-present olive oil in Greece. Paprika, uncommon in Greek cuisine, is a staple, particularly in the region bordering Hungary, and often as not the main meal at Easter will be lamb paprikash stew.

My second Easter in Serbia is fast approaching. At times of high holidays, it is nice to be in a country where most people are your coreligionists, and move to (and are moved by) the same traditions, along with interesting differences.