Each of the three principal combatants, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece, had heavily invested in modern weaponry, to be used with deadly effect in the First World War, most notably the machine gun. At sea, Greece’s navy, while smaller than the Ottoman, was more than a match for her foe in skill and technology. As Turkey had just concluded an inconclusive war with Italy and had expected an Italian landing in Asia Minor, much of her army was in Asia rather than Europe, and the Greek navy could be counted on to impede seaborne reinforcements.

Geography dictated strategy. Bulgaria, just north and east of Constantinople, would strike at Thrace and eastern Macedonia, Greece would strike northward towards Epirus and western Macedonia, and eastward at the Aegean Islands still under Turkish rule. Serbia would strike south into the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, Kosovo, Albania, and what is now FYROM. Serbia and Bulgaria had a vague agreement as to division of territory, but between Bulgaria and Greece the basic rule was “you get what you capture,” hardly a sustainable alliance strategy.

Bulgaria, with the largest Balkan army, threw the hammer down on the Turks in Thrace, winning overwhelming victories at Kirk Kilisse (Saranta Eklisies) and Lule Burgas. At the latter battle in particular, the Bulgarians absolutely annihilated the Turks with heavy artillery, machine guns, and mass bayonet charges. The Turks fell back to the suburbs of Constantinople and the Times of London speculated that King Ferdinand of Bulgaria would be proclaimed the Tsar of a new Byzantine Empire, comprising a federated Balkans.

Serbia moved southward, achieving significant victories at Kumanovo, near Skopje, and then Monastir, just north of today’s Greek frontier. They reunited Kosovo (Serbia’s Byzantine-era heartland) with Serbia and overran most of northern Albania, together with the Montenegrins.

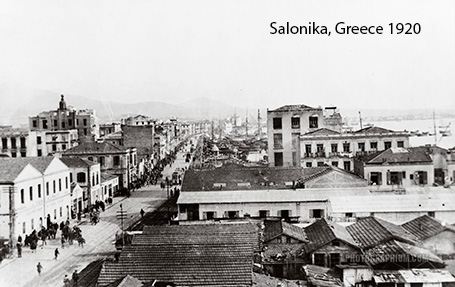

Greece struck northward, sweeping the Turks aside after some hard fought battles near Mount Olympus and reached Macedonia’s jewel, the city of Salonika, just a day’s march ahead of the Bulgarians. The army also laid siege to Ioannina and pushed into western Macedonia, meeting their Serbian allies essentially at the present Greece-FYROM frontier. Greece later pushed into Northern Epirus with once again the goal to create a common frontier with Serbia on the southern Adriatic.

While Salonika was the prize of the Balkan Wars, taken by Greece, arguably her greatest victories were in the Aegean. Forgive me, as a Hydriot, for tooting my island’s horn, but as in the War of Independence, Hydriot naval officers figured prominently in Balkan Wars. A Hydriot torpedo boat captain Nicholas Votsis penetrated the Turkish naval cordon in Thessaloniki and blew a Turkish cruiser to shreds. His compatriot, Admiral Pavlos Koudouriotis, grandson of Admiral Koudouriotis of Revolutionary War fame, mauled the larger Turkish fleet in the Battle of Elli, preventing reinforcements to be sent to outflank the Bulgarian and Serbian armies, and opening up nearly all of the eastern Aegean Islands to Greece, which were picked off individually, or, in the case of Samos and Ikaria, liberated themselves. Early in 1913, the naval Battle of Lemnos would turn the Aegean Sea virtually into a Greek Lake. Crete was already united with Greece de facto; de jure recognition would come with the peace treaty. Cretan gendarmes immediately began policing Thessaloniki and would prove invaluable in the coming year.

By the year’s end, Turkish rule had disappeared from Europe except for the Gallipoli Peninsula (soon to become famous in World War I), Constantinople, and the besieged cities of Adrianople, Ioannina, and Scutari. Bands of Turks and Albanians still harassed the Balkan League forces, and vicious atrocities were committed by all sides, just as all performed acts of heroism. Albanians in Valona, with Austro-Hungarian and Italian support, declared independence in late November, but this was still hardly a certainty. Turkey was clearly on the ropes, and the Great Powers of Europe, caught off guard by the rapid shift in affairs, conferred internally and in concert about what to do.

Ominously, the Balkan Allies were already beginning to show signs of strain. Greeks and Serbs lowered their rifles at each other, as Allies, once the Turks between them were vanquished, but where Bulgarians collided with Greeks and Serbs, incidents abounded, particularly in Thessaloniki, where the Bulgarians sent in a detachment for “joint occupation.“ As always, the Balkan states showed what they could achieve by unity, and then the process of squandering began, as the Turkish threat which they had skillfully and successfully dispatched was replaced by inter-Orthodox infighting that lends weight to the word “balkanization.” That tragedy would unfold in the coming year, 1913.