The Liar and the Lady, 66 Years later

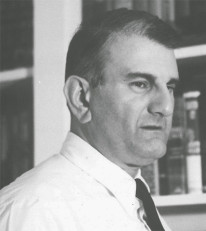

Harry Mark Petrakis

by Harry Mark Petrakis

On Sept. 30 of this year, my wife Diana and I had been married for 69 years. In the third grade of our Greek parish school, she remembers me trying to convince my teacher I had lost my homework using a phrase she was hearing for the first time, “on my word of honor.” I remember her as a skinny girl with large dark eyes that seemed to overpower her face.

When we met again in our teens, I was stunned at how she had bloomed. She had become shapely and taller, her face adorned by her great black eyes, her raven-black hair tumbling from her temples across her shoulders.

We began to date, casual evenings sipping chocolate phosphates at Reader’s Drug Store near the University of Chicago. We also spent hours talking aimlessly on the telephone.

After completing several business courses, Diana went to work as a hostess in a restaurant and, as I feared, began attracting other suitors. The most dangerous was a young clone of Robert Redford, with tousled blond hair and six feet of imposing height.

Studying my own face in the mirror gave me little reason for reassurance. My nose and jaw fought one another for prominence. My oversized ears, one lobe half inch longer than the other, gave my head a lopsided appearance.

Desperate to find a playing field on which to compete, I drew upon the fertility of my imagination. A visit to a grocery became an Odyssey with my inventing various colorful characters I described to Diana.

In 1940, Europe at war, I had been taking fencing lessons at an academy in Woodlawn. One student was a youth of German origin named Helmut. We had fenced one another with the customary rubber-tipped foils. I made the match more ferocious to Diana, who worried that Helmut might wish to harm me.

Trapped in my own exaggerations, to keep the drama mounting, I told Diana that after a violent argument Helmut challenged me to a duel with bare blades.

Diana pleaded with me to refuse the challenge. I told her honor demanded I accept. The duel was set for the following evening after the academy had closed.

My preference was to claim I had mortally wounded Helmut, but that posed a problem in how I had disposed of the body. I moved reluctantly to a more benign conclusion.

The morning after the fictional duel, I taped a piece of gauze to my chest and stained the edge of the gauze with iodine to simulate blood. I phoned Diana and told her the duel had ended in a draw after Helmut and I had inflicted minor cuts on one another.

She insisted I come see her at once. I shamefully savored her tear-stained face as I showed her my bloody bandage.

We were married in the autumn of 1945. For the first year we lived with my parents and then moved to a third-floor studio apartment. Our windows looked out on a huge courtyard that in summer resonated with tongues like the Tower of Babel.

In 1948 our first son, Mark, was born. In the following years I worked in the steel mills, on the railway express, on a beer truck, pressing clothes for a cleaner, selling real estate.

All this time, haphazardly, with fitful starts and finishes, I was writing. Year after year, my manuscripts were returned, first with printed rejection slips then with a few scrawled words of encouragement. But I sold nothing.

My father died and a second son, John, was born. These were hard years for our family. Bills piled up. There were sometimes bitter accusations about my failure as a provider, my inability to hold a job for more than a few months. We talked of separation.

In December of 1956 I sold my first story to the Atlantic Monthly. About that time, we moved to Pittsburgh to a job as a speechwriter for U.S. Steel. A third son, Dean, was born in Pittsburgh and my first novel was published. Elated and overconfident, ignoring the warnings of others, I moved back to Chicago to write full time.

Our income my first year as a freelancer was $1,600 and the second year $2,400. Our family survived on the generosity of our nephews, Leo, Frank and Steve Manta, who renovated an old house their father owned in South Shore where we lived rent-free. We also ate two to three times a week with my wife’s parents or other relatives.

In the mid-1960s, my third novel, A Dream of Kings, became a best seller, a Book Club selection and was translated into a dozen foreign editions. We sold the movie rights and moved to California where I wrote the screenplay. As with so many writers who had gone to Hollywood, the experience wasn’t a happy one.

Once again choosing novels and stories, I moved my family back to the Midwest. In the following years, I wrote and published additional stories and books.

A single stroke of good fortune in writing does not last forever. Through the 1970s and 1980s, we lived precariously on my lecturing as well as writing. We were helped by two years I served as writer-in-residence for the Chicago Public Library, and then two years as writer-in-residence for the Chicago Board of Education.

In 2006 Diana suffered a stroke. While making a handy recovery, she remained frail, with only a fraction of her previous energy and strength. Both of us aware that none but the early dead are spared the ravages of aging; we limped through our 80s together.

In these last years I have done much of what she once did for me, but she would have responded the same way. Meanwhile we try to retain our sense of humor.

At times when I have coaxed her through a stern regimen of therapy she finds painful, she refers to me as “Caligula,” the brutal Roman Caesar who murdered numerous relatives. We laugh then, and I am reminded of the lines from Yeats, “Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes, their ancient eyes are gay.”

In old age, everyone becomes a historian. Looking back, I mark that our life has been a shared journey. Diana cared for our family during those hours I spent at the typewriter and the computer. We celebrated the growth of our sons, grieved the death of our parents, and had the fulfillment of holding my published books, the bindings that held the fragrance of fresh paper and ink.

I understand how much she influenced and enriched my stories. Many women characters I created are facets of Diana, whether chaste as the biblical Ruth or sensual as Bathsheba. Wherever I traveled, she was the lodestone that drew me home.

Many other couples linked together a long time have conflicts and resolutions equally as dramatic. But in the way that no fingerprint or snowflake is the same, each love story is unique.

Diana and I have now lived together so long and loved one another so well; the name of one can never be uttered without, in the same breath, speaking the name of the other.

Reprinted from the Chicago Sun-Times

0 comments