Greek-American Hero, Author and TV Commentator Jack Jacobs

by Marcia Haddad Ikonomopoulos

Jack during the Vietnam War

The Medal of Honor is the highest military decoration presented by the United States government to a member of its armed forces. Created during the Civil War, the recipients “must have distinguished themselves at the risk of their own life above and beyond the call of duty in action against an enemy of the United States.” Most of the recipients did not survive to receive the award. Of an estimated 2,709,918 Americans who served in Vietnam, only 277 have been deemed worthy of receiving the Medal of Honor. One of those recipients was a Greek-Jew, Jack Jacobs, whose paternal side of his family hailed from Ioannina.

Squeezed in between two interviews at 30 Rockefeller Plaza (Jack is a military advisor for NBC/MSNBC) Kehila Kedosha Janina (Greek Romaniote Synagogue at 280 Broome Street in NYC) was honored to welcome Jack Jacobs to speak to our community and sign copies of his book, “If Not Now, When?” While most of the post presentation questions centered on national security, in light of the recent terrorist acts in Paris and Africa, my main area of interest was Jack’s Romaniote background and growing up in a Greek-Jewish world.

Jack was born in Brooklyn to a father from a family of Jewish immigrants from Ioannina and an Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish mother, but was most influenced by his Greek-Jewish grandmother who lived in Williamsburg. It was her cooking that he enjoyed, foods that his Ashkenazi mother never quite learned to make. Jack related, to the knowing laughter of the audience, the story of how his mother had requested that his grandmother write down her recipes before she died, which she did. After his grandmother passed away, his mother attempted to make the traditional Greek foods. It was a disaster. His mother had never really adjusted to Jack’s father marrying a non-Greek Jewish girl and it was as if her hand reached up from the grave. She had purposefully left out important ingredients to ensure the failure of the cooking, something this audience who grew up in the same world could relate to.

Jack Jacobs speaking at Kehila Kedosha Janina (the Greek Romaniote Synagogue)

Jack’s father, David Jacobs, born in 1919 in Brooklyn, spoke nothing but Greek until he was five years old, not at all uncommon for Jews from Ioannina. David learned English in school but the language spoken at home remained Greek. Jack, the first born son, in the tradition of Romaniote Jews, was named after his papoo (grandfather) and was affectionately called the pasha. After his parents moved to Queens, Jack continued to visit his grandmother every weekend, as the children were dropped off at nona’s house to give the parents a break. (While most Greeks call their grandmothers yiayia, Greek Jews used nona.)

David & Rebecca Jacobs wedding

As with most immigrant families, the Jacobs had high hopes for their children. Jack’s parents had assumed that their bright, if a little rambunctious, son would become a professional, a lawyer or an accountant. Even though Jack’s father had served in the United States Armed Forces in the Pacific during World War II, David Jacobs was less than thrilled to learn that his son would be going to Vietnam.

Jack had joined the ROTC while attending Rutgers University in New Jersey. He felt that “everyone had the responsibility to make some contribution to the defense of the Republic,” and, in addition, appreciated the small monthly stipend of $27, especially after marrying at 18 years of age. When joining the ROTC in 1962, the prospect of war seemed far away but, as Jack neared graduation in 1966, realizing that he was in desperate need of a job to support his wife and child, the looming nature of war with Vietnam became a reality. He approached his commander and requested active duty. To do so, he would have to enter as a commissioned officer and this required committing oneself to active duty for three years instead of the normal two he would have to serve as a reservist. Then, his choice of which branch to request became a deciding factor. He chose the infantry. He could have chosen a noncombat commission but felt that if he was going to serve, he was going to fight. He requested to become a paratrooper and was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division. Jack makes it clear that his decision in this instance was based on money. “Jump pay” was an additional $110 a month in additional to his pay as a new lieutenant. He now had two children and a wife to feed, so for a little over $300 a month, Jack headed to Vietnam to risk his life for his country.

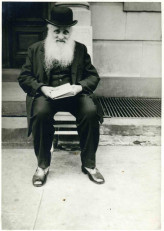

Jack’s father’s grandfather, born in Ioannina

One has to understand from the beginning that, although choosing what appears to be a traditional, old-fashioned, old school choice of profession at a time when many of his contemporaries were doing everything possible to avoid the draft, Jack is not that easy to define. Yes, he believed in service to his country but his insights into the army and what can be learned from his participation, shows that it is not easy to stereotype Jack. Take his views on military service: “The nature of military life consists of vital tasks like setting objectives, allocating resources, and solving problems, all things that can be accomplished by most young enlisted people but evidently difficult to do by elected officials and highly compensated business executives.” Or take his views on voting: “I don’t vote. I don’t want to encourage any of them.”

Jack arrived in Vietnam as an advisor, a position he did not relish, but did give him the ability to speak some Vietnamese, since an advisory position required a crash course in the language. The Tet Offensive, a response on the part of the Viet Cong to increased attack by US forces, lasted from January 30, 1968 through June of 1968. It was by all definitions the largest military operation conducted by either side up to that point in the war. On March 9, 1968, working as the assistant battalion advisor, his battalion came under intensive fire from the Viet Cong. According to the US Army report on Jack’s heroics, “As Jacobs called in air support from his position with the leading company, the company commander was disabled and the unit became disorganized due to heavy casualties. Although wounded himself by mortar fragments to the head and arms, Jacobs took command of the company and ordered a withdrawal and the establishment of a defense line at a more secure position. Despite impaired vision caused by his injuries, he repeatedly ran across open rice paddies through heavy fire to evacuate the wounded, personally saving a fellow advisor, the wounded company commander, and twelve other allied soldiers. Three times during these trips he encountered Viet Cong squads, which he single-handedly dispersed.”

Jack Jacobs speaking at Kehila Kedosha Janina (the Greek Romaniote Synagogue)

Jack was issued the Medal of Honor on October 9, 1969 for “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” The medal was formally presented to him by President Richard Nixon. In addition, he won two Silver Stars, 3 Bronze Stars and 2 Purple Hearts. Not bad for a 5’4” soldier who was born in Brooklyn. Jack kidded that his height was an asset since he was such a small target. After being awarded the Medal of Honor, Jack returned to active duty. The military was hesitant to assign Medal of Honors winners to combat roles but Jack was not finished fighting. He used subterfuge to return to combat. After leaving active duty, he taught at West Point Military Academy for three years, from 1973-1976 teaching international relations and comparative politics, finally retiring from the military in 1987. Jack then went into private business in finance.

David Jacobs, Jack’s father as a young boy

Jack’s reflections on the Medal of Honor, and those who have received it, tells much about the man. “Recipients of the Medal of Honor really have little in common. They have been from every state, economic station, and ethnic group. But they have shared a strong sense of duty and of purpose and the motivating burden of personal responsibility at the perilous point of decision. They feared death, but their biggest fear was failing themselves, their friends, and their nation, and thus they have been no different from the tens of millions of the other men and women who have served in uniform.”

It was no surprise that MNBC and its affiliate, NBC, chose Jack as military advisor. After all, he is among the most highly decorated soldiers from the Vietnam War era, having earned three Bronze Stars, two Silver Stars, two Purple Hearts and the Medal of Honor. In addition to MNBC and NBC, Jack has been on the Colbert Show. His humor and wisdom is excellent combination for the intelligent wit of Colbert. When meeting Jack, you quickly forget his small stature. His energy, dynamic personality and intelligence shine through. As a Greek Jew and as an American, I am so proud of Jack Jacobs. He has served us well. He has made us proud.

Marcia Haddad Ikonomopoulos is Museum Director at Kehila Kedosha Janina, the one and only Greek Synagogue in the Americas.

0 comments