The Athenian: Elizabeth Boleman-Herring, an American-Greek

Alexander Billinis

We met the way most people do these days, digitally, due to common interest in all things Greek. After reading her work, our friendship deepened via online correspondence and her patient mentoring of my midlife attempts to turn writing from a passion into a side vocation.

I am sure we had “met” in print before, decades earlier, through her writing. My parents, on our annual family trip home to Hydra, would often stop for a couple days of “jet lag therapy” at the Athens Hilton. In every room, “The Athenian: Greece’s Engish Language Monthly” was propped up in a place of honor on the coffee table, and my American-born Greek mother, happy for once not to struggle with reading Greek, would often lift a copy to take with her. As Deputy Editor of the magazine (now, like so much media of substance, defunct), Elizabeth Boleman-Herring’s non-fiction musings on Greek reality would put my mother in stitches. Hers was a language and mentality my mother readily understood.

Today, as I read her book Greek Unorthodox: Bande à Part & A Farewell To Ikaros, I relish the time capsule of a Greece I knew in my youth. The author’s experiences of day-to-day life in Athens (which she calls her Greek chorio or hometown), though separated from my own by nearly three decades, make me nod in agreement, amusement, and break into a nostalgic smile or, often enough, despair.

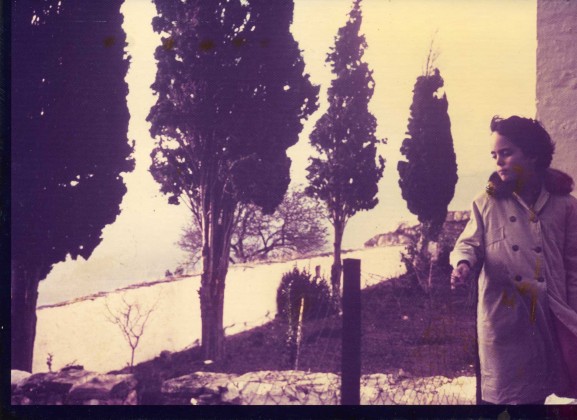

Elizabeth on Hydra (c. 1961, photo by F. Jack Herring)

Boleman-Herring describes her work as “a portfolio of snapshots and ‘group-selfies’” taken from within her Athenian parea. She calls herself “a minor Jane Austenopoulou sitting in a Monastiraki kafeneion, musing privately.” Having lived in Athens, and stolen moments from the reality of life and work in the quiet cool of identical Athenian kafeneia, I think, “She wrote this book for me.”

For the author, always writing in English shot through with highly idiomatic Greek phrases, Greece is the consuming passion, her greatest love.

Her introduction to the country came very early, at age ten, when her father, a psychiatric social worker and academic from Southern California, moved the family to Greece on a Fulbright grant. After the upscale bubble of early-60s Pasadena, the jarring realities of post-war Greece marked the author for life. For many expats at the time, Greece was exotic, still barely post-colonial, and cheap.

“At ACS [The American Community Schools], in Halandri,” Boleman-Herring says, “where I attended 6th and 7th grades, I represented a third class of students. The ruling class was made up of the children of US military personnel, and the ‘untouchable’ class comprised those with Greek surnames. Since my family, unaligned with the US embassy or the bases, lacked ‘colonial privileges,’ and since my educated parents identified with their Greek colleagues and students, I was in free fall, neither one nor the other. In Athens, I learned what it was to live in the shadow of a colonial power, and what it was to be colonized–as a grade school student. It was a lesson I could never unlearn, an ugly reality I could never un-see.”

For the Herring family, their three-year stay in the country necessitated a deep dive into the real Greece, a deeply hospitable yet socially shredded country still reeling from the recent civil wars, World War Two, and the Asia Minor Disaster, all events too close—both chronologically and societally—for anyone’s comfort.

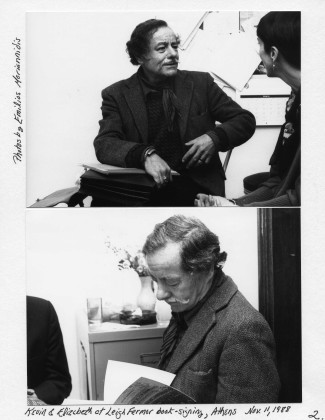

Elizabeth with Kevin Andrews, Athens (Photo by Emil Moriannidis)

As her father conducted interviews with women survivors of the two-part Civil War, Elizabeth had no choice but to digest it all, and found “she could never go back” to a sheltered American reality afterwards. Her Greek reality was and is “visceral, not romantic,” she says, and after her stint in Greece as a child, no matter what her passport said, she would self-identify as Greek. Like other Greeks, either in Greece or throughout the vast Diaspora, she feels that her Greek identity was less about choice than about experience and, somehow, inevitable.

The 1970s found her returning to Greece with an MA in Literature, working, writing, and living in Athens and on Mykonos as a local. Her early childhood intimacy with Greece and Greeks broadened, and she married Diaspora Greeks (twice: from Istanbul; then, Rhodesia), lived all of the trials and triumphs of an Athens expanding at an unhealthy and dysfunctional pace, and a Mykonian village still caught in the previous century as the island itself throttled towards becoming the world capital of chic and hedonism. Her writing embodies, without guile, a time capsule of a culture undergoing momentous change.

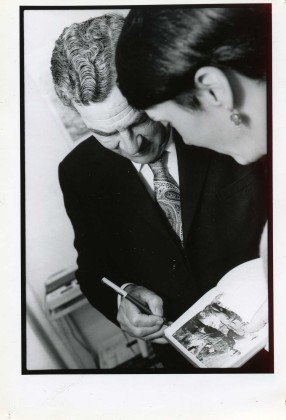

Boleman-Herring is part of the rarefied tribe of mid-20th-century Anglophone Philhellenes which thrived in an era that began just before World War Two. It was then that a brooding American expat named Henry Miller spent a few transformative months in the country, writing of its beauty, history, landscapes, and one Olympic personality in The Colossus of Maroussi, a memoir dedicated to the Greek literary giant Yorgos Katsimbalis. Then the war came and Greece’s heroic role in war and resistance sealed an emotional—though not political—bond between the Philhellenic Allied officers who fought with the Greek resistance and their counterparts. Patrick Leigh Fermor immediately comes to mind as the British don of this group, and Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese and Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece are easily two of the best accounts of life in Greece during that era on the heels of the war.

Elizabeth, who knew and published Leigh Fermor, experienced the Greece he describes when she was a child, and then again as a woman in her 20s and 30s. The two writers met, and collaborated when she founded “The Southeastern Review: A Journal of The Humanities in the Southeastern Mediterranean.” While Leigh Fermor was an important mentor, in both style and spirit, Boleman-Herring’s work is more like that of another American turned Greek, Kevin Andrews.

Like Elizabeth’s father, Andrews came to Greece via a Fulbright grant, in his case to study at the American School of Classical Studies, where he produced an exemplary piece of literature and scholarship, The Castles of the Morea, a lovingly erudite work describing the many fortresses of the Peloponnese.

Elizabeth with Patrick Leigh Fermor, Athens (Photo by Emil Moriannidis)

It was, however, more typical of Andrews to focus, in his prose, on the myriad working parts of Greek culture as opposed to the monuments of just one era. Written in roughly the same period, The Flight of Ikaros: Travels in Greece During the Civil War recounts the fully bilingual author’s travels and relationships in Greece in the throes of the Civil War. No work captures the horrors of the conflict and the simmering tensions better than this book, which is as relevant today as when it was written almost 70 years ago.

While Leigh Fermor’s love for Greece is undoubted, he remained a Briton with a British, almost colonial, attitude towards his Greek home and subject matter. Such an attitude was common among many expats in Greece, but Andrews is exceptional in that he integrated into Greek life and culture, becoming a Greek citizen in 1975 and a tireless campaigner against the Junta. He railed against all modernization on an American model, and lamented the watering-down of Greek culture.

In this, Elizabeth resembles him, herself taking Greek nationality in 1982 and her work standing as a sharp riposte to American “colonial voices” as she calls them. In books such as Vanishing Greece, she documents the loss of the traditional Greece that she loves. The coffee table book, a collaboration with Patrick Leigh Fermor and photographer Clay Perry, was translated into many languages, and remained in print for decades, touching a raw nerve of shared loss. But it was in Andrews that Boleman-Herring found her greatest inspiration—and literary love. It was almost fated that two such Philhellenes would meet hard and fall in love, but fate also cut the relationship short when Andrews died in a swimming accident. In her memoir, A Farewell To Ikaros, Boleman-Herring provides a fitting tribute to her late fiancé, and her writing reflects that love as she preserves his legacy.

While Leigh Fermor’s writing is better known by Greek-Americans, in large part because of his famous war exploits on Crete, the work of fellow Greek-Americans (or American-Greeks) Boleman-Herring and Andrews should be required reading.

They speak our unique language, came of age in America and, using the tools available in two languages, as outsiders turned insiders, describe the reality of our shared motherland, in all its Classical, Byzantine, and Modern variety. They write with love and orexi—but “love,” as Fermor once wrote when praising Andrews’ work—“has not made [them] blind. Shallow Philhellenism gets it in the neck.” Their depictions of reality in Greece may be jarring at times and, at other times, radiant, but they are always authentic.

Take their books with you to Greece and, in an Athenian kafeneion, surrounded by the capital’s polyglot babble, you will find yourself nodding, smiling, and, occasionally, tearing up.

Selected Books by Elizabeth Boleman-Herring:

Greek Unorthodox: Bande à Part & A Farewell To Ikaros. Rivervale, NJ: Cosmos Publishing, 2005.

Vanishing Greece. Photo. Clay Perry. Intro. Patrick Leigh Fermor. London: Conran Octopus, 1991. Coffee-table book. In multiple translations and editions, 1993-present.

0 comments