- The Brothers Gerazounis: Engineering the Lifeblood of Buildings

- The Hellenic Initiative Summer Youth Academy Empowers Underprivileged Children Through Sports

- CAPTAIN MARIANTHI KASDAGLI: Charting her own course at sea

- Oscar nominee Lorraine Bracco of ‘Goodfellas’ is having ‘More Fun’ than ever before

- Voice And Vision: Grigoris Maninakis, 50 Years Of Greek Music In America

Alabama’s Alex Gulas: a Pioneer for Racial Justice

by Ike Gulas*

Born November 22, 1923 in Birmingham, Alabama, the youngest of nine he was raised in the Norwood neighborhood which is where many of Birmingham’s ethnic population such as Greeks and Italians lived. His father, Theodore Gulas was a restaurateur having opened Birmingham’s first Greek owned hot dog stand in the early 1900’s. Alex attended and graduated from Phillips High School in Birmingham and enrolled in Birmingham Southern College in 1941. Near the end of his first semester Pearl Harbor was bombed and he enlisted in the Army shortly thereafter. His service led him to the Pacific Theater where he fought in the Battle of Okinawa (one of the bloodiest battles of WWII). During his life he would often say, “We were told we would be invading Japan next where the casualties were expected to be in the millions. I didn’t think I would be going home if we invaded Japan. Thank God Truman dropped the bomb.” His service during World War II was a source of pride throughout his life and he would often refer to it. Even later in life when his memory began to slip he would always remember his days in the service.

Alex Gulas is reading the president’s charge at the installation of his son Ike (right) as the new Supreme President. Left,he departing Supreme President Gus James.

Upon his return from the war, Alex anticipated he would return to his college studies; however, his father had different plans. Theodore took the money Alex was sending home from the service and bought a restaurant for him to open located directly across the street from Birmingham’s Legion Field (nicknamed the Football Capitol of the South). Legion played host to numerous college and professional football games well into the 90’s and was the annual host of the Iron Bowl pitting Alabama vs. Auburn. Alex saw an opportunity to capitalize on this reputation and named his restaurant the Quarterback Drive-In and included two football shaped windows in its construction. Alex sold the restaurant in the early 1950’s to pursue another venture. Ultimately, the Quarterback Drive-In would become the iconic Tide & Tiger and play host to thousands of tailgating football fans throughout the years. To this day it remains open and the football shaped windows are still in tack.

The 1950’s were exciting times. The war had ended and jazz was all the rage so Alex decided to open a jazz club in downtown Birmingham named the Key Club. During those years Birmingham, like many southern cities, was segregated. There were also so-called “Blue Laws” in place to prohibit Sunday liquor sales. However, the mostly white country clubs were allowed to serve liquor on Sundays to its members. Alex wanted to open on Sundays so he purchased a private club license and sold memberships to the Key Club. One Sunday while pouring a customer a drink, he was arrested for violating the Sunday Blue Laws. He challenged the arrest claiming that the license he held allowed him to serve drinks on Sundays just as a country club could serve them to its members. The trial court ruled in his favor, but the state, appealed and eventually the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the decision allowing private clubs to serve alcohol to its patrons on Sundays.

As mentioned earlier, Birmingham was segregated and many of the city leaders were KKK members or promoters of segregation. As recounted by Alex, one Sunday evening a friend of his brought a young African American school teacher and musician named Avery Richardson to the Key Club to see if he could get a job. Alex told Avery to go on stage and sing. He sang Rambling Rose to an all white audience that night and received a standing ovation. That, by all accounts was the first time an African American musician performed to an all white audience in a public forum in the State of Alabama. Alex hired Avery Richardson that night to lead his house band and thus was the beginning of not only a business relationship but a lasting friendship. During those years the infamous Bull Connor was Commissioner of Public Safety which was akin to Chief of Police today. He was a frequent visitor to the Key Club and knew Alex, having served in the Jaycees and American Legion with him. During those tumultuous years Connor would order raids on the Key Club to dissuade Alex from letting African Americans play there, however, according to Richardson, “Alex never backed down and always stood with the musicians.” Many would become famous household names and would later recount how they got their start at the Key Club. Many went on to play in bands led by Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie. A few of the musicians who played the Key Club over the years were Erskine Hawkins (composer of Tuxedo Junction), Joe Guy (husband of Billy Holiday) and Cleve Eaton. In addition, Bobby Darin was a frequent entertainer at the Key Club as well.

In April 1956 Nat King Cole was scheduled to perform at Birmingham’s City Auditorium to an all white audience. Shortly after beginning a group of KKK members rushed the stage and tackled Cole assaulting him. The police were able to subdue the attackers but Cole was injured and could not continue the performance. He was scheduled to perform at the Key Club later that evening but chose to leave town for his safety. In addition to the raids ordered by Connor, Alex would also receive death and bomb threats for allowing African American musicians to play in his club. In a 1993 Birmingham News article, Alex stated, “We were harassed. People didn’t want them playing there. I was 27 years old and wasn’t worrying about the racial unrest I was causing. I was single and enjoyed the jazz musicians. I didn’t mind the harassment because it was the right thing to do.”

In 1990 Avery Richardson nominated Alex for induction into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. In that same Birmingham News article, Richardson is quoted as saying, “He was a very kind and gentle man when it was not popular to be that way to blacks. It would have been more difficult without club owners such as Alex Gulas. He didn’t have to do it. It was more of a risk than a benefit.” Gulas was the first club owner and non-musician to be inducted into the hall of fame. Richardson added in the article that in those years he tried to buy a house in a nice neighborhood but did not show enough income, so Alex co-signed the mortgage allowing him to purchase the home.

During those years Alex was also civically involved in Birmingham. As a member of the Birmingham Jaycees he rose through the ranks to serve as Vice President. In another example of how racially divided Birmingham was during that time, Alex ran for President of the Jaycees upsetting the favored candidate and becoming what would have been the first Greek American to hold that position. However, the powers that be would not let that happen and called for a new election where they brought in ringers to insure their candidate would win. In addition to the Jaycees, Alex was also active in the American Legion and the Order of AHEPA.

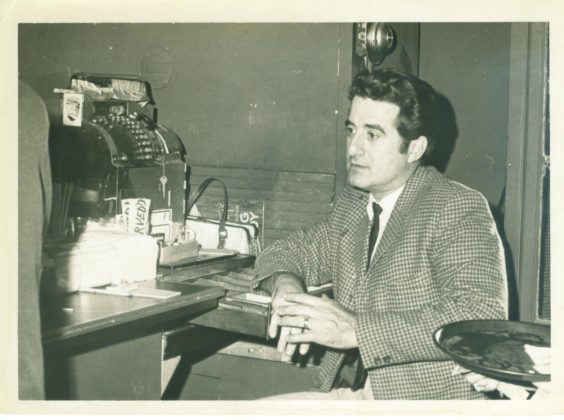

In 1961 Gulas, no stranger to controversy, opened the Blue Note Lounge. The Blue Note was a restaurant in the front and a nightclub in the back. During those years burlesque dancers were popular and the Blue Note would be the first club in Alabama to showcase these entertainers from throughout the United States. Once again, Alex was breaking new ground and the Blue Note would play host to Birmingham’s business community. Many couples, doctors, lawyers and professionals would frequent the Blue Note which was the closest one could get to a New York feel in Birmingham. In 1961 at the age of 38 Alex married Helen Jebeles who would forever be the love of his life. They soon bought a home in Birmingham and a year later had Ike, their only child. Throughout most of the 60’s they would run the Blue Note as one of Birmingham’s most successful businesses. However, the constant late nights were not how they wanted to raise a family and Alex was looking for a way to earn a living yet spend nights at home.

In 1961 Gulas, no stranger to controversy, opened the Blue Note Lounge. The Blue Note was a restaurant in the front and a nightclub in the back. During those years burlesque dancers were popular and the Blue Note would be the first club in Alabama to showcase these entertainers from throughout the United States. Once again, Alex was breaking new ground and the Blue Note would play host to Birmingham’s business community. Many couples, doctors, lawyers and professionals would frequent the Blue Note which was the closest one could get to a New York feel in Birmingham. In 1961 at the age of 38 Alex married Helen Jebeles who would forever be the love of his life. They soon bought a home in Birmingham and a year later had Ike, their only child. Throughout most of the 60’s they would run the Blue Note as one of Birmingham’s most successful businesses. However, the constant late nights were not how they wanted to raise a family and Alex was looking for a way to earn a living yet spend nights at home.

As mentioned earlier, Theodore, Alex’s father opened the first Greek owned hot dog stand in Birmingham in the early 1900’s. His hot dog was topped off with a special sauce he either invented or brought with him from his hometown of Kounoupia, Greece. Later at the Quarterback Drive-In Alex would learn how to make the hot dog sauce as well as his father’s chili and special hot beef topping. Throughout his career in the club business, Alex always thought he would one day open a hot dog stand and once again serve his father’s recipes. In 1970 that dream became a reality when along with his brother-in-law, Dino Jebeles, Alex opened Dino’s Hot Dogs in downtown Birmingham. Dino’s was an instant success and soon more locations were opened throughout the greater Birmingham area. Doing so allowed him to close the Blue Note in the early 70’s and concentrate on building his new venture. By the mid 70’s, there were 12 Dino’s Hot Dog locations in Central Alabama.

For the better part of the 70’s, Alex was busy tending to the multiple locations he built and as he desired would be able to spend nights with his family. At the same time, Helen’s health (she suffered from Sickle-Thalassemia) was worsening and she was spending more and more time in and out of the hospital. Luckily, Alex came from a family of nine siblings (6 boys and 3 girls) and most of them lived within a few blocks of each other which made it possible for someone to look after Ike while Helen was in the hospital. In addition, Alex’s mother-in-law, Katherine Jebeles moved in with the family after her husband’s passing in 1972. But Alex insisted on being by his wife’s side each and every time she was hospitalized, spending countless nights sleeping in a recliner in her room then getting up each morning to see to his businesses.

Eventually, around 1980, he would sell most of his locations and settle into working the one in Homewood, Alabama which is a quaint suburb of Birmingham. His hot dog stand was located on the main street where pedestrian traffic is the norm with a homey neighborhood feel. It was here, the last place he would work, that he touched countless lives with his generosity and hospitality. In 30 plus years at that little hot dog stand, which was maybe 900 square-feet, he made each and every customer feel as if they were the most important customer in the world, never differentiating between those with standing and wealth or those who could not afford the price of a $1.25 hot dog. Corporate CEOs stood next to UPS deliverymen at the same counter enjoying Alex’s food and especially his conversation. He prided himself on giving free drink refills long before it was the norm, canvassing each inch of the dining room, dish towel in hand cleaning tables, sharing a word with his patrons and insisting on getting them a refill. Behind the counter he always had a bucket of candy that he would pass out to the multitude of kids who would visit Dino’s with their parents. And for the adults he would always offer a sampling of his delicious baklava which sat under the glass display tray in front of the register.

Generations of kids grew up at Dino’s over the years; many would celebrate birthday parties there and return years later with their children to celebrate their birthdays. School kids would write papers about Mr. Alex and his everlasting smile and generosity. Alex would look after the many little old Greek men and women who lived in the neighborhood who would stop in on a daily basis for a visit. Many joke that Dino’s was the Greek internet before there was an internet. Don Siegelman, the Governor of Alabama who loved Alex, would hide out from his security detail in Dino’s to grab a hot dog and visit with him. He never turned down a local high school or college dance or sport team selling ads or sponsorships. He never met a stranger. The hospitality and respect he extended to his customers and Dino’s was the same he extended to those jazz musicians being discriminated against in the 50’s and 60’s.

Those who knew him would tell you, Alex Gulas was one of the most kind, compassionate and giving individuals you would ever meet. It was not unlike him to stop his car and give a home-less person money to eat or to prepare a sack full of hot dogs and give them to a family who might not be able to afford them. A testament to the man he was happened just days before he passed. In the emergency room suffering from pneumonia, the hospital administrator came in to have some papers signed by the family. As she waited, she inquired about this gentleman who was lying on the hospital bed. She felt as if she knew him. When told he used to own Dino’s Hot Dogs she smiled and told the family that 25 years before as a young nurse she took care of his wife Helen and fondly remembered him bringing hot dogs and baklava to the nurses and staff each night he would come visit. The smile he brought to that woman’s face and to all those whose lives he touched is exactly how he would have wanted to be remembered.

Ike Gulas, son of Alex Goulas, is practicing law in Birmingham, Alabama and he is former Supreme President of the Order of AHEPA.

0 comments