The Importance of Being Hydra

Alexander Billinis

We Hydriots are seldom lacking in pride for our island. It is, after all, a time capsule away from the crush of car and concrete, a cubist amphitheater of perfection surrounding a port where man and nature coalesced to create the perfect picture. That is the Hydra of today, the fabulous—though pricey—holiday, and one where the demons of overdevelopment are held at bay by the historical preservation codes strictly enforced.

Yet Hydra was so much more, if we look to the past.

Here we need not jump back two millennia, just a couple hundred years. In 1819, immediately prior to the Greek War of Independence, Hydra was one of the richest islands in the Mediterranean basin. Its ships plied the Mediterranean and Black Seas, moving the commerce that began to recover from the decades of the Napoleonic Wars. During those wars, the Hydriots gained fortune running the British blockade of the French-held ports, and in fighting off the Barbary pirates of Libya and Algeria—against whom the United States, incidentally, fought its first foreign war—the Hydriots combined their naval with martial skills.

Hydra by that time had largely the silhouette of today, with its stately, Italianate mansions combining Aegean cubism with more than a touch of Tuscan, Venetian, Marsaillaise, and Triestine. The hardy Hydriots had been to these places, which were also home to large Greek communities.

It is hardly unusual for Greek islands to possess the aristocratic houses of shipping families. Many islands have proud nautical histories stretching, in some cases, to the Classical period. What is remarkable about Hydra, however, is that the island’s naval prowess rose from practically no roots whatsoever, yet the island then became the prototype for the Greek island shipping dynasties which followed.

It started in Hydra, and it started from virtually nothing at all.

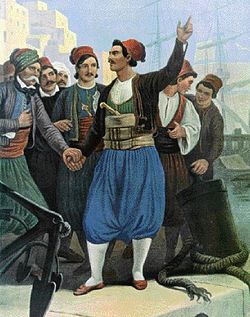

Antonis Economou, a Hydriot captain and member of the Philike Etairia, who ousted the Turkish appointed governor and brought the Revolution to Hydra (Painting by Peter von Hess)

Hydra, notwithstanding a name derived from water, is largely blue-grey granite and barren. Parts of the island have some pine cover, but it is largely a near-lunar hulking mass. While the surrounding basin has been densely inhabited and part of history for well over five millennia, Hydra bears virtually no archeological trace from the Mycenean, Classical, and Roman eras, and only a few Byzantine coins found at Episkopi, the one somewhat arable patch on the island, constitute the most important find from history. The island probably supported a few pastoralists or people who had a reason not to be found, but only as the Ottoman Empire weakened and the neighboring Peloponnesus raged with warfare between Ottomans and Venetians in the late 1600s and various revolts in the 1700s did the island receive an influx of population, often as not speaking Arvanitika (a dialect of Tosk Albanian) as well as Greek.

As refugees on a barren land, they did what Greeks have done from time immemorial, and took to the sea. Their first ship, said to be built in 1657, was an ungainly vessel, according to tradition its lines and halyards were fashioned of plaited vines. Trial and error, and borrowing, no doubt, on the greater skills of other Aegean islanders and the still-ubiquitous Venetians, the Hydriots were quick studies, and a century later they were building two-masted brigs with 250 tons’ displacement and taking the commerce of the Eastern Mediterranean with them.

The rise of Hydra coincided with two key geopolitical events. The first was a series of Russo-Turkish wars, which brought Russian power into the Black Sea and an increasing interest by the Orthodox “Big Brother” for the Greeks, Bulgarians, and Serbs under the Turkish yoke. The Russians encouraged Orthodox Ottoman subjects to move to their newly liberated Black Sea coast, and tens of thousands did, founding or bolstering Greek communities along the coast, which would work and supply the growing Greek merchant fleet. The wise and wily Hydriots refused to take part in the Orlov Revolt in the Peloponnesus, a Russian-inspired fiasco that ended up drenching the land in blood. “Mother” Russia was, as ever, a fickle parent to her Balkan “children.”

The shrewd Hydriots did, however, gain from both the Turks and the Russians. The Turks appreciated the Hydriots’ wealth and naval prowess and gave the island a virtual autonomy in exchange for a periodic levy of Hydriot sailors for the Turkish fleet. The Russians secured, in the Treaty of Kucuk Kainardji, the right for Hydriot and other Ottoman Christian ships to fly the Russian flag—the first flag of convenience! The Russian flag provided a protection for the Hydriot ships against the Turks and others, as well as tax and tariff benefits. This lesson was not forgotten by Greek shipowners in the 1930s and after.

As the Russian and Ukrainian steppes, long a killing field between the Russians and the Turks, yielded to the plow, the fertile black earth produced bumper crops, and Greek brokers in Odessa and a dozen other ports filled the hulls of Greek ships as they turned grain into gold. In the Napoleonic Wars, these Hydriot ships, along with those of neighbor Spetses, ran the British blockade of Spanish, French, and Italian ports to feed their inhabitants with Russian grain—for a fortune.

The British targeted these islanders, and when one wily Hydriot captain was captured and brought to Admiral Nelson, the hero of Trafalgar asked the captured man, “What would you do to you if you were in my shoes?” Without a thought, the Hydriot replied, “I would hang you.” Impressed by the captain’s combination of bravery and sheer audacity, he replied, “If I ever see you again, that’s what will happen.” The reprieved captain was Andreas Miaoulis.

Hydra enjoyed its golden age with the end of the Napoleonic Wars. They had wealth, power, contacts with the West, and a privileged, autonomous status in the Ottoman Empire. They were no doubt well aware of the movement for Greek independence; the Philike Etairia, the secret society for Greek independence, was founded in Odessa in 1814, and the Hydriots knew the Russian port well. There were Hydriot members of the Etairia, but many of the wealthiest shipowners worried about the effect of a war at home on their fleets and fortunes. They were not wrong.

When the Revolution against the Turks broke out in the neighboring Peloponnesus, the Hydriots prevaricated. As is often the case, the wealthy were less moved by national spirit than the middle classes, and it was Antonis Economou, a Hydriot captain and member of the Philike Etairia, who ousted the Turkish appointed governor and brought the Revolution to Hydra.

Once in, the great shipowners and their fortunes were plowed into the fray, and along with the two other “nautical islands,” neighboring Spetses and tiny Psara in the Eastern Aegean, they succeeded in clearing the Aegean of the Turks. The role of the Hydriot navy was pivotal, and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that without this island, the Revolution probably would have failed.

But the golden age was over, and only glory remained. The Hydriots were among the chief bankrollers of the independence struggle, and war is always costly, particularly when combined with civil wars within the independence struggle and a penchant for financial mismanagement. Successful battle with the Turks and their Egyptian allies was costly in terms of ships and lives, and far too many of both lay at the bottom of the Aegean Sea.

Hydra port today

Hydriots began to leave the island, sometimes for the Diaspora centers they knew well or further afield to America, but most often to Pireaus and Athens. In an era before naval insurance, many great fortunes were ruined, and a generation after independence a Hydriot remarked to then-Queen Amalia that Hydra produces nothing but “prickly pears in abundance, excellent sea captains, and a few Prime Ministers.”

Ironically, the country they helped to birth may have strangled the Hydriots’ shipping energy. The Greek state was chronically in debt and did little to develop commerce and infrastructure. Hydriots retained their status and stature due to their revolutionary record, and often they were co-opted into the state system which combined most of the vices of the Ottoman bureaucracy and few of the virtues of a Western governmental system.

The torch lit by the Hydriots did not go out, it merely passed to other islands, notably Syros and Andros in the central Aegean, the island of Chios (under Ottoman rule until 1912), and Cephalonia (under British rule until 1864). In all cases, it was a combination of local and (especially) Diaspora capital which funded the ships’ construction. Combined with the Greeks’ innate nautical skills and a highly cosmopolitan Diaspora, the course for Greek shipping was set. Nearly 200 years later, the Greek merchant fleet, under a variety of flags and always with a deep Diaspora involvement, is the world’s largest.

Hydra is, and should be, proud of her role in the development of the Greek Merchant Marine, and for her sacrifices for Greece.

Honor is due.

0 comments