- Leading HANAC: Stacy Bliagos on Community Service in New York

- The Hellenic Initiative Celebrates Record-Breaking Weekend in New York

- Building the Future: HANAC’s 53rd Anniversary Gala Honors Advocates for Affordable Housing and Community Care

- Leona Lewis: Las Vegas residency ‘A Starry Night’

- Emmanuel Velivasakis, Distinguished Engineer and Author, Presents His Book at the Hellenic Cultural Center

George Papayannis Joins NYC’s Cathedral School and Makes It the School to Watch

The Cathedral School in New York City has been a venerable institution for 70 years, but now it might become the school to watch with the addition of a new Head of School last July who is already an education superstar.

“I’ve lived in New York, I know the environment, so I said let’s serve our church and make The Cathedral School a national model,” says George Papayannis, 42, with a stellar career already as a graduate of Teacher’s College, Columbia University, and Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, as well as years of teaching in Boston and Colorado and leadership roles throughout the country working to improve teacher performance and schools.

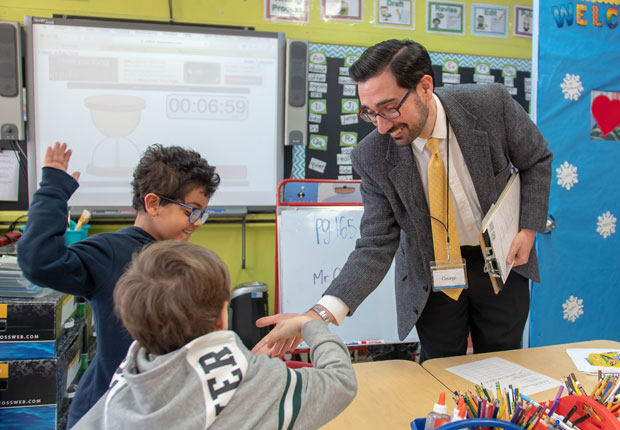

Mr. George high fives two second graders on his way out of the class. Photo: Sotiris Michalatos/TCS

And he thinks The Cathedral School can be both a stalwart of classical education and a leader in the breathtaking evolution of hands-on learning using modern technology—in fact, he calls that the very model of a classical education.

“If you go back 2000 years, there was a lot of hand work,” he calls it. “There was a lot of building. There are ancient structures that still stand today as a testament to the skill of those cultures. And in them there was a balance of head work and hand work to create a balance in building.”

In that classical spirit, he says he not only wants to maintain and elevate the academic standards of the school (it offers Latin as well as ancient and modern Greek and sends its graduates to the top high schools), but to balance the learning with projects using laser cutters, milling machines and 3-D printers that can produce anything the kids can imagine.

“The kids are not only reading modern Greek literature like Samarakis, but they’re also reading trade books and finding out not only what industry professionals do but doing those things themselves,” he says.

Mr. George is measured by a second grader using meter sticks. Photo: Sotiris Michalatos/TCS

He wants students to build a makerspace in the art studio at the school similar to the Fab Lab model devised by MIT so students can design and create models using digital fabrication tools.

“We have a strong visual arts program and we want to grow that,” he says. “As a school our first priority is to offer a great education.”

And part of that, he says, is having kids use digital and analog technologies “to make prototypes of whatever is in their heads.”

The school board, he says, is open to these innovations, because while The Cathedral School is affiliated with the Archdiocesan Cathedral church, it is independently-funded and can chart its own course.

Mr. George is measured by a second grader who paces the perimeter around him. Photo: Sotiris Michalatos/TCS

At the same time, because the school population has transitioned from entirely Greek when it was founded in 1949, to more inclusive and international today–nearly fifty-percent of students are non-Greek and non-Orthodox–he believes the school has an opportunity to educate the community at large on what it means to be Greek and Orthodox.

“Half of our kids aren’t Greek or Orthodox,” he says, “and we see that as an opportunity to teach people who we are. Many Americans associate ‘Greek’ with Plato, Socrates, mythology, and if they’ve been paying attention to the news, they know about the financial crisis in Greece. But the 2000 years of Greek history in between the ancient and the modern Greek world is not taught much in U.S. schools: the Byzantines or Asia Minor, for example. As part of fulfilling our priority of offering a great education, we should take the opportunity to teach people who we really are.”

The practical side to his teaching philosophy comes from his years working as a structural engineer (his degree from Drexel University is in architectural engineering) and also volunteering as a mentor to high school students in New York City. Using his background he helped them design buildings through ACE Mentor Program, which was founded in part by his employers at Thornton Tomassetti.

George Papayannis speaks on a panel on innovation on Jan 18, 2019, at the Museum of Science, Boston. Photo: Eric Workman/MOS

“Every other week we taught kids how to design buildings,” he explains. “We paired a team of building design and construction professionals with a team of students and taught them about what it means to be on a building team: with an owner’s representative, an architect, a mechanical engineer, a structural engineer, and a construction manager. We were teaching the kids through a design project how a building gets designed and built. We worked on mixed-use high rises, a firehouse, an aquarium, and we used actual properties for our constraints.”

He liked the mentoring so much that he left his engineering day job to become ACE’s Assistant Executive Director for Greater New York. While doing that, at the age of 26 he also enrolled at Teacher’s College to get his teaching credentials.

And when he got out he started teaching in Colorado.

“I taught in middle school for a couple of years, then came back East when my dad got sick. The folks in Denver are very warm and I still keep in touch,” he says.

He was also close to the church and over the years had volunteered at various camps here and in Greece, including Ionian Village in the Peloponnese and Thari Monastery in Rhodes, and closer to home at various camps in Pennsylvania, Portland, and Seattle.

“And what I noticed in working at the camps was that there were commonalities,” he says. “From an educator’s viewpoint I saw areas where we could improve and I saw it as my obligation to support the church and put my talents towards that.”

After his father died, he moved to Boston to study religious education at the seminary. And while there an opportunity opened up for him to teach physics in the Boston Public Schools, and he went to work at Fenway High School. A year later he was invited to be an adjunct professor of environmental science at Hellenic College, which he did for five years, and he co-authored a teacher guide called Of Your Mystical Supper: The Eucharist.

He worked eight years in the Boston Public Schools as a science and engineering teacher at Fenway High School and the Boston Arts Academy, before getting a scholarship to Harvard to get his principal credentials.

He then came back to Boston to challenge himself yet again by going to the city’s lower-performing schools and organizing teams to improve them.

“I wanted to put myself in more challenging schools and see what it takes to fix them,” he says. “My role was leading teams and coaching teachers. I was part of the administrative team and what I learned is that the kids come from the same place, the teachers are smart, but the difference comes down to processes: the higher-performing schools had layers of processes in place implemented by strong teacher teams: the lower-performing schools were missing those.”

And then with his wife Melissa (who had also attended the Greek summer camps and once worked at the U.S. Embassy in Athens) he moved on to his next challenge: founding his own Orthodox school and bringing to it the lessons he had learned throughout his teaching career.

“My wife and I, we’re both children of Greek immigrants, born and raised in the U.S., but we both lived in Greece, and for the last couple of years we had been researching what it would take to start an Orthodox school,” he says. “We wanted to start a family (they have a young daughter) and were thinking, What kind of environment do we want our daughter to grow up in?”

They got involved with the Orthodox Christian School Association and were invited to join their board. And they had friends who suggested instead of starting a school from scratch why not find an existing one and make it better.

“So when this opportunity (at The Cathedral School) came we thought, let’s go do this,” he says. “Let’s serve our church and see what we can do to help grow it.”

GEORGE PAPAYANNIS

As Head of the School his duties are overreaching: he has to do the administering, the recruiting, and the fundraising (it helps that his wife is in fundraising), and report to his school board. The school has a faculty of 20 teachers to a ratio of 107 kids from preschool to eighth grade, and Greek is taught every day to all grades.

“We have families who are not Greek and they come to us because they want their child to learn another language and they like the Orthodox side of what we do,” he says. “They like the value system that we share, and even if they’re not Orthodox, they appreciate how we’re treating their children and their family.”

His own family comes from York, Pennsylvania, where he grew up with two brothers, and where his grandfather Yiorgo settled after immigrating from Megali Panagiea, Halkidi, and he started working at the Cole Steel factory. His father Theoharis was trained as a car mechanic in Greece and also worked in factories in York. One of George’s brothers saw his aptitude in math and science and suggested he try architectural engineering.

“And I didn’t know any better so I said, sure, it sounds great” he says.

He got into architecture competitions, his mother Anna bought him books about buildings, and then he got a scholarship to study at Drexel. When he graduated, he wanted to work for “the coolest companies that were designing buildings” and landed a job in New York at Thornton Tomassetti and live just nearby from where he now works at the school.

“It’s great being back in New York,” he says, ”because I get to see all these buildings I was enamored with as a kid and I always get a kick checking out the skyline and which cranes are doing what kind of work.”

He and his wife are also avid hikers, and he is active on several boards including Chair of The Innovators group at the

Museum of Science in Boston. He is also in demand throughout the country for professional development workshops.

But, of course, his main focus now is making The Cathedral School the model school he envisioned when he took the job, one that, he says, “in five to seven years will be known across the country and around the world and educators will come to learn from us.”

0 comments