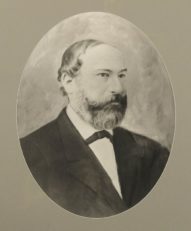

Nicholas Benachi, Founder of the First Orthodox Church in the US

Alexander Billinis

On many occasions in this magazine I have focused on Greek communities in the Diaspora or interesting “Hellenes without Borders.” This month, I will do both. We will meet Nicholas Benachi, the founder of the first Greek Orthodox Church in the United States.

While Greeks have spread far and wide in the United States, most of us instinctively guess that the oldest Greek communities must be in the North, and more specifically a city like New York or other usual suspects such as Chicago, Boston, or Philadelphia. The correct answer is New Orleans, where the first Orthodox Church was founded just after the Civil War, in 1864.

A bit of history makes this more understandable. New Orleans in the middle of the nineteenth century was one of the busiest ports in America. Situated at the mouth of the Mississippi River, which effectively drained the whole center of the United States, New Orleans was the key hub on the country’s commercial highway prior to the railroads becoming ubiquitous.

While we normally associate the Greek merchant fleet and diaspora more with the twentieth century and such celebrity tycoons as Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos, the truth is both shipowners were atypical parvenus rather than normative Greek shipping and merchant magnates. The Greek merchant and shipping traditions were hundreds of years old by the time Onassis and Niarchos emerged as its paparazzi darlings. Parts of Greece, particularly islands such as Chios or Cephalonia, or regions of Macedonia and Epirus, had a long tradition of commerce, either via ship or overland, and over the course of many generations had built up very successful, discreet merchant dynasties.

Nicholas Benachi

Nicholas Benachi was born in Chios into one such extended commercial family. The Benachi (Benaki) family had many branches and its members could be found in business in places as diverse as India, Alexandria, Odessa, Trieste, and London. The growing American republic could not fail to get these Greeks’ attention, particularly the large river port moving massive amounts of commodities from the continent’s interior and most notably King Cotton, which reigned supreme in the period before the Civil War. Greeks had generations of commercial skill and unsurpassed nautical abilities, both in the open sea and, through generations of Danube piloting, on rivers. New Orleans was a natural place for Greeks.

Nicholas Benachi arrived in New Orleans in 1850. He immediately set himself up in the cotton trade, working for the Ralli trading company, fellow Chiots in an interlocking set of commercial families. Though cotton cultivation was based on the evils of the slave plantation system, it made fortunes for everyone not actually doing the backbreaking work. As was typical of Greeks involved in Diaspora trade, Benachi also secured an appointment as a consul, in his case for the Kingdom of Greece, in 1854. This was subsequently ratified near the conclusion of the Civil War by President Lincoln in 1864.

Benachi House

The small but often wealthy Greek (and other Orthodox) communities in New Orleans acutely felt the absence of a church, a problem common to the small but growing Orthodox populations gathering in key American sea and river ports such as New Orleans, New York, Charleston, and Boston. Greek merchant communities always invested in the establishment of a church as a spiritual and cultural reference point, from the time the first Byzantine refugees founded San Giorgio Church in Venice. In Benachi these efforts found a champion with the clout to make it happen.

In 1864, Benachi and three other Orthodox New Orleanians, Constantine Kililis, a Greek from Asia Minor, Michael Draskovich, a Serbian from Bosnia, and Dimitrios Botassi, from Spetses, established Holy Trinity Eastern Orthodox Church, the first Orthodox Church in the United States. Holy Trinity was decidedly multiethnic and multilingual, with priests who could conduct liturgy in Greek and Church Slavonic. A copy of the church charter from 1901 required chanting in Greek, Russian, and Syriac.

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church

Holy Trinity Church itself was a modest clapboard wooden building, described by the New Orleans Times Picayune as “a plain, unpretentious frame structure, similar to country churches in Louisiana.” This also fits the Diaspora pattern; often enough Diaspora Orthodox Churches conform to architectural norms of the host country, from the Renaissance style of San Giorgio in Venice to the Baroque of Greek and Serbian churches in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Beyond being a benefactor of the Church, Benachi strove to build awareness among the people of New Orleans about the trials and travails of the emerging Greek state, which had yet to incorporate his home island of Chios into the motherland. Like others, he also sent sums back to Greece, whether for educational purposes, or to assist in the armament of the Greek military and revolutionary forces in various parts of Greece not yet redeemed. Here again we see a diaspora pattern common to Greek merchants in Marsailles, Alexandria, Vienna, and to Greeks abroad today who are interested in the affairs and struggles of the homeland.

Many Greeks left New Orleans during the disruptions of the Civil War, particularly cotton merchants who were instrumental in establishing Egypt as a major cotton exporter. Another Times Picayune article, from 1872, laments the diminution of the Greek merchant class, “[who] commanded an influence in financial and mercantile sectors . . . that made them respected by the boldest operators.” Benachi remained in New Orleans, a feature of society and the business community until his death in 1886.

The Times Picayune mourned the loss of “an old and valued citizen, one who for a quarter of a century figured prominently in the business circles of the city and was known always and everywhere as a man of the strictest integrity and honor.” The obituary also referred to his consular service and to his role in the establishment of the Greek Church in the city. His role in Greek and Orthodox America is a little known and discreet one, belying his role and prominence, and perhaps it is how he might have wanted it. Born in Chios before the Greek War of Independence, he would have seen his island ravaged by war and massacre. He was part of a merchant culture that persisted despite war and repression, who navigated politics, conflict, and commerce with the same skill as piloting their ships.

He is one of Greek America’s Founding Fathers.

0 comments