Talkin’ About the Revolution

Alexander Billinis

What good is it to talk about ourselves—to ourselves?

I am paraphrasing the words of a good friend who, like me, has spent years conveying the Hellenic message outward, to the wider community.

How and why, would people listen to our story?

This is the question that every marketer must ask, and, as a university lecturer, I have to ask myself this same question every time I get in front of class, either in person or, for much of the past year, virtually.

Context is Key . . .

There is no question that the Greek Bicentennial is going to mean more to us who are Greek than it will mean to others. It is here that a subtle shift from commemoration to contextualization makes all the difference. The “Why this is Important” instead of just “What Happened.”

There is no problem with being enthusiastic when you tell a story. In fact, you absolutely have to be engaged in your story. The listener instinctively responds and knows when you are invested or not. Perhaps the biggest problem with Greece’s official 2021 organization—and its appendages in the Diaspora—was its obvious lack of spirit and style a term described best in Greek as “Peitharcheia.” The absence of peitharcheia will never win you hearts and minds.

However, peitharcheia combined with context often will. Reminding the listener and reader that the Greek Revolution was the West’s “Cause Celebre” of the age, and that even as the governments and business interests of the West hardened their hearts to the Greek cause, the common people rallied to Greece’s freedom. The common people, but also the “rock stars” of the era, people like Lord Byron.

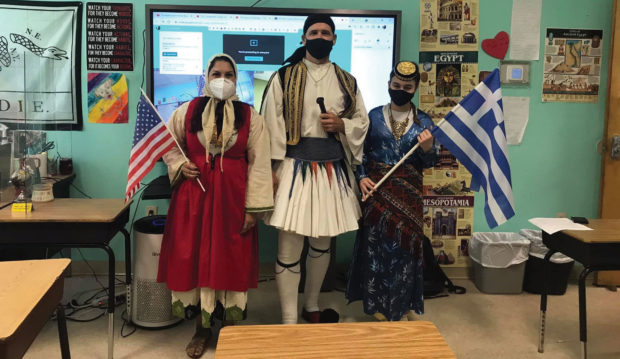

Middle school teacher Ms. Hawley (left), Eric Hill (middle) & Eric’s daughter (right) previous to the EMBCA (w/ introduction by founder/president Lou Katsos streaming in from New York) presentation “The Greek Revolution of 1821 is YOUR history … because it is American history.” Streamed from the classroom to 9 Plato Academy middle schools: TarponSprings, Clearwater, Tampa, St. Petersberg, Largo, Palm Harbor, Trinity & Pinellas Park.

Or the second nation in the Western Hemisphere to gain its independence, via a slave revolt, Haiti, which was also the first nation to recognize Greece’s independence in 1822. There are the black American Philhellenes who saw in Greece’s enslavement a parallel to what was going on in the US, and they set off to fight for Greece’s freedom.

There is Daniel Webster, the fiery and learned American Senator, who admonished his colleagues for not doing the right thing and assisting the Greeks who were fighting the same enemy as the Americans only a dozen or so years before, in the Barbary Wars. William Washington Townshend, nephew of the Father of our country, who gave his life in the rebirth of another. He is buried on my island, Hydra. Even to a bored class of Introduction to US History, connecting Greece to such names and events makes an impression.

There is one of my favorites, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe of Massachusetts, who organized aid for Greece, administered to the sick and wounded in country, and as a skilled duelist, fought valiantly both the Turk and the corruption of some of the Greek revolutionaries. Dr. Howe’s love for Greece did not end at independence, he helped bring orphans to America, and later in life, returned to help the Cretans who sought time and again to unite with free Greece.

Fewer people are aware that Howe, and others, in part horrified by the enslavement of Greeks particularly after the Chios Massacre and Ibrahim Pasha’s depredations in the Peloponnesus, returned to America determined to exorcize the demon of slavery in the United States.

These are just one of many examples, of how our Greek story is also an American story, one that needs to be told.

So how is this done?

Luckily, there are plenty of fora for such discussions. The East Mediterranean Business Culture Alliance (EMBCA) for the past several years has sponsored programs and outreach to the wider community as well as more Hellenic community centered. One of my favorite EMBCA events was a night of music comparing Rebetika to the Blues, in cooperation with the Greater Harlem Chamber of Commerce.

While my university work rarely covers issues concerning Greece and the Greek community, my outreach work into the local and larger community, both individually and with EMBCA, has been successful. I have spoken about the Battle of the Atlantic from a Greek perspective at local museums, at EMBCA events, and at Clemson’s Lifelong Learning Center which caters to the large retiree community in the area.

I am currently in the middle of a series at the Lifelong Learning Center talking about “The American Revolution Exported: Greece 1821,” where I guide the participants through the events of 1821 via an American prism, and I tie past with present. Other good friends, colleagues from the EMBCA, have taken to telling a version of the same story to multi-ethnic American schoolchildren attending the nine Plato Academy (Hellenic) middle schools in Florida.

Sister Cities Programs linking American and Greek municipalities are another means of pairing the American story with the Greek. I was particularly proud, last year, to help broker such a relationship between my ancestral island, Hydra, and the “Greekest Place in America,” Tarpon Springs. The desire of people to connect is innate in our wiring, and the lockdowns of this past year, if anything, make people more interested to form relationships. Why not join your American home with your Greek homeland, and let both learn from each other?

Have the conversation. Make it contextual—and people will listen.

0 comments