The Greek American Abolitionists

by Dean Kalimniou*

“Ye sons of burning Afric’s soil,

Lift up your hands of hardened toil

Your shouts from every hill recoil

Today you are free.”

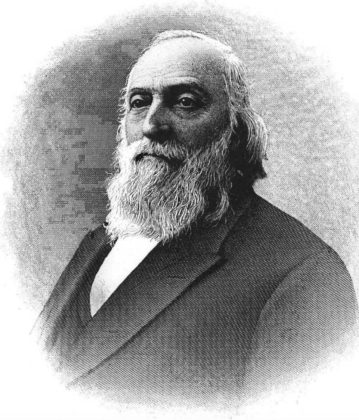

When John Celivergis Zachos penned the above verses in 1862, he was on Parris Island, formally appointed by the Boston and New York Education Commissions to prove that emancipated slaves could be educated. With 400 freed slaves on a plantation, Zachos was known to recite poetry to them, teaching them to read and helping them overcome years of years of torture and psychological abuse. In many respects, Zachos was ideal as an appointment. Having been exposed to slavery himself during the Greek Revolution, his harrowing experiences would prove the catalyst for his life-long advocacy for emancipation and equal education rights for African Americans and women.

Having lost his father, freedom-fighter Nicholaos Zachos and then his mother Euprosyne, in 1824, Zachos and a number of other orphans and emancipated child slaves were taken to America by philhellene and surgeon Samuel Gridley Howe, in order to be educated. Enrolled at the Mount Pleasant Classical Institute in Amherst Massachusetts, Zachos and the other young Greek refugees were instructed by Gregory Anthony Perdicaris, a survivor of the 1822 massacre of Naousa. Showing great promise, he completed a Teaching Degree and a Medical Degree and went on to found the Literary Club of Cincinnati.

Serving as a surgeon in the American Civil War, he was an outspoken advocate for the necessity of the abolition of slavery and for the rehabilitation of African American slaves, devising programmes for their integration into society as equals. He also supervised an experiment in re-settling recently freed slaves on land abandoned by planters. The experiences that he gained were applied to educating immigrants and women and he went on to pioneer a phonic system of teaching reading, publishing the primer: Phonic Primer and Reader. An avid inventor, he obtained a patent for a spinal support as well as for a stenotype used for printing legible English text at a high speed.

John Celivergis Zachos

When Zachos left for America as a child, he was accompanied by Garafilia Mohalbi (Garifalia Mihalbei), a young girl who had lost her parents in the massacre of Psara. Sold as a slave to a Turk in Smyrna, she was redeemed by an English merchant, a Mr. Langdon who arranged, through Samuel Gridley Howe, her passage to America. Sadly, she did not live long, dying of tuberculosis at the age of thirteen in 1830, but her plight moved the American public a great deal. American painter and miniaturist Ann Hall created a miniature portrait of her as a Greek slave girl which was later popularised as an engraving by Edward Gallaudet. American poet Lydia Sigourney wrote a poem in her honour, while in 1843, American poet Hannah Flagg Gould wrote the poem, “Garafilia’s Picture”, which was featured in her book The Golden Vase A Gift for the Young. In turn, writer Sarah Josepha Hale featured an article in her book Woman’s Record Or, Sketches of All Distinguished Women, relating to Garafilia.

In the 1850s, Carl Hause commissioned Carl Gartner to compose a mazurka for piano to honour her memory, while it became the fashion for ships to be named after her and parents to give her name to their daughters. So pervasive was her posthumous fame that she inspired American sculptor Hiram Powers to travel to Europe to witness the slave trade. It was while in Florence that he began to sculpt the popular sculpture The Greek Slave, which held great symbolic meaning for abolitionists. So synonymous did Garafilia become with the American abolitionist movement, that she even makes an appearance in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin” a book published to document the veracity of the depiction of slavery in her iconic anti-slavery novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” where Stowe writes: “I was in Smyrna when our American consul ransomed a beautiful Greek girl in the slave-market. I saw her come aboard the brig ‘Suffolk,’ when she came on board to be sent to America for her education.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe obtained much of her information about Garafilia from Christophorus Castanis’ 1851 book “The Greek Exile.” Enslaved during the massacre of Chios and forcibly converted to Islam, Castanis was also one of the orphans sent to America by Samuel Gridley Howe. Educated at Yale and Amherst College, Castanis delivered many lectures on the subject of his experience of slavery, using his own circumstances to call for the abolition of the institution in America. His accounts also referred to the fate of the other orphans rescued by Howe and he went on to publish numerous works about Greek philology and mythology, as well as his 1849 book, Oriental Amusing, Instructive, and Moral Literary Dialogues: Comprising the Love and Disappointment of a Turk of Rank in the City of Washington, which the Washington DC newspaper “The Republic” considered “…is made the vehicle, in a conversational form, of conveying the expression of the author’s republican sympathies on behalf of Greece and Turkey, as well as of discussing some philological questions, intended to prove that modern Greeks pronounce their language as the ancients did..”

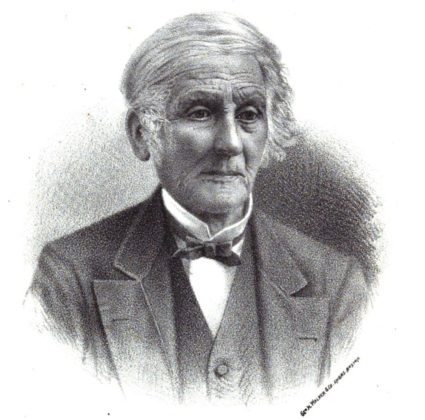

Photius Fisk

Perhaps the most influential of all the Greek-American abolitionists was Photius Fisk. Born Photios Kavasalis on the island of Hydra, he was taken to America in 1822 by missionary Pliny Fisk where he was educated at Amherst College. Having secured a position in Capodistrias’ government, he travelled to Greece and was directed to await the outcome of the Battle of Navarino. Instead, Fisk tried to secure passage back to America, ending up instead on the island of Martinique where he witnessed chattel slavery and was horrified by the experience, which he related to his own childhood exposure to the horrors of Ottoman slavery. After successfully securing passage to New York, he stopped in Wilmington, North Carolina, where he witnessed American Slavery, an institution which he later wrote, was more horrific than that on the island of Martinique.

As a result of his experiences, he became a fervent abolitionist, teaming up with such preachers as the Reverend Samuel Hanson Cox who preached that Jesus was dark skinned. He became a US Navy Chaplain and campaigned for the abolition of flogging on US ships, which would benefit slaves working on them. As a result of his endeavours, he was frequently abused and spat upon. Unperturbed, he continued his endeavours, fighting not only against physical slavery but also what he called “mental slavery”. During the outbreak of the American Civil War, he travelled to Boston to aid the abolitionist cause. In 1861, he donated a substantial amount of money to abolitionist William Shreve Bailey. After the war, he amassed close to forty thousand dollars for the purposes of providing for destitute former slaves and also raised funds to erect monuments to important abolitionists such as Henry Clarke Wright in Providence, William Shreve Baily in Kentucky and Jonathan Walker in Michigan.

Having donated all his income to his last surviving family members in Greece on a trip there in 1873, Photius Fisk returned to the United States and continued his philanthropic work. Large sums were donated to the Perkins School for the Blind, which was run by the Epirot Michael Anagnos, and who provided early training to Helen Keller. In 1881, he donated one hundred twenty-nine volumes of Ancient Greek books to the University of Iowa. In 1884, he donated one thousand dollars to the Paine Memorial Company to support lectures and also gifted it his valuable collection of pictures and artifacts. At his death in 1890, he bequeathed his entire fortune to the poor and destitute, specifically naming The Coloured Woman’s Home in his will as a beneficiary and directing the executors of his will to seek to relieve the plight of destitute African Americans.

Dealing with the trauma of prejudice, discrimination, massacres and slavery, the Greek-American abolitionists were following in the footsteps of their ancient ancestors. In his “Messiniakos” Ancient Greek philosopher Alcidamas of Elaea advocating the freeing of the Messenian helots, stating: “God has left all men free; nature has made no man a slave.” In this vein, the Greek-American abolitionists were able to capture the sympathy of the American public, already sensitive and sympathetic to the struggles of the renascent Greek nation for freedom from persecution and for the right to self-determination. They were able to channel that sympathy so as to facilitate public empathy will all persecuted people, regardless of creed or colour. In so doing they became valuable and influential members of the anti-slavery movement. It is upon that rich and profound legacy that all diasporan Greeks, campaigning for social justice, can freely draw for to paraphrase Photius Fisk, these heroes, “though often outraged and martyred for [their] principles, [were] never conquered, suppressed or discouraged. It was through the efforts of such Heroes that the world had been made fit for the abode of Humanity.”

*) Dean Kalimniou (Kostas Kalymnios) is an attorney, poet, author and journalist based in Melbourne Australia. He has published 7 poetry collections in Greek and has recently released his bi-lingual children’s book: “Soumela and the Magic Kemenche.” He is also the Secretary of the Panepirotic Federation of Australia.

0 comments