The tragedy with the 4,000 Greek children who were sent to the USA during the Cold War (1950s-1960s)

Professor Gonda Van Steen

“Imagine someone who chooses clothes from a fashion catalogue. This is exactly what happened to the infants from Greece at that time. Americans ordered a baby, and if they were not satisfied for a number of reasons – such as the child’s illness, or quarrels with the other siblings – they gave the baby back,” says Professor Gonda Van Steen to NEO.

by Kelly Fanarioti

It was a simple email of a few lines, with which a 20-year-old American student went searching for his Greek roots, that took Gonda Van Steen – a Belgian-American classical scholar and neo-Hellenist, who specializes in ancient and modern Greek history, language and literature – into the new, uncharted terrain of adoption stories in Greece that are emblematic of Cold War politics and history.

Professor Van Steen is the first woman to hold the Koraes Chair of Modern Greek and Byzantine History, Language and Literature. She is also Director of the Centre for Hellenic Studies at King’s College London. To write her book about the Cold War adoption history of Greece, she engaged in a thorough investigation that started in 2013 and lasted seven years. During her visits to archives in Greece and across the USA, she searched meticulously through hundreds of public records on passports and visas issuances at the time. Van Steen recently published her book titled “Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece: Kid pro quo?” in Greek translation as Ζητούνται παιδιά από την Ελλάδα: Υιοθεσίες στην Αμερική του Ψυχρού Πολέμου. The Greek version was issued by Potamos Publications in November 2021.

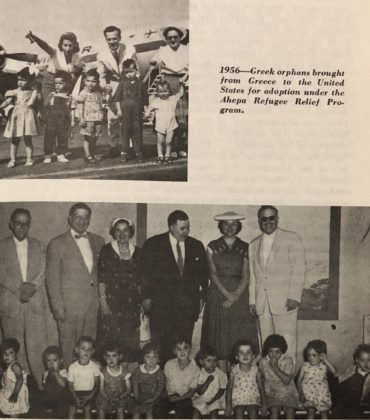

Caregivers and beaming Ahepans, Leber

“I was trying to answer the 20-year-old student’s questions about the adoptions of his mother and aunt by an American family, but I was faced with a serious issue: I did not know anything about these adoptions, despite my many years of study, as I had never come across a relevant reference in the literature,” she said. She further explained that the young man who opened the door for her to this unknown page of modern Greek history was the grandson of Elias Argyriadis, who was executed on the same day as Nikos Belogiannis in March 1952.

“The adoption of Argyriadis’ children was political, because then the Greek state did not want Communists’ children, so they were given away. Unfortunately, there were more such cases in addition to the children who were sent away for adoption because social stigma rested on their unwed mothers,” she explains.

The massive wave of adoptions of Greek children by wealthy American couples hit a peak from 1950 to 1962. Many babies who were the fruit of a forbidden love were placed in nurseries, and from there various lawyers undertook the work of placing them abroad for a fee. Some lawyers who pursued adoptions for personal profit sent brochures with photos of the babies to American families, for them to choose the child they liked best.

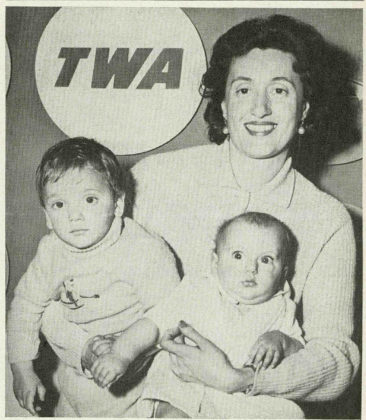

Jane Russell, 29 Oct 1958

“Imagine someone who chooses clothes from a fashion catalogue. This is exactly what happened to the infants from Greece at that time. Americans ordered a baby, and if they were not satisfied for a number of reasons – such as the child’s illness, or quarrels with the other siblings – they gave the baby back,” Professor Van Steen says to NEO. She adds: “In such cases, the lawyers who acted as intermediaries did not bring the child back to Greece, but they looked for another family and made even more money from the transaction.”

By 1955, lawyers received approximately 500 dollars for each adoption. But from then onwards, demand for white and healthy babies on the other side of the Atlantic sharply increased as childless couples in the midst of the American baby boom felt socially stigmatized. Thus, the fee for an adoption from Greece reached 3,000 dollars by the end of the 1950s.

What she finds particularly sad is the fact that most lawyers’ motivation was purely financial and that there was absolutely no assessment of the suitability of the adoptive American families. “I met some adopted people who ended up in the United States and who were in some instances raped or brutally beaten by their adoptive parents. Keeping a child in an institution is definitely not good, but a thorough evaluation of the suitability of the adoptive families was lacking for many years and that was a huge mistake, too.”

Wilson, Lamberson, adoptees

They are still looking for their roots

Van Steen’s research has reconnected many families who were separated for decades. Indicative is the case of a 66-year-old woman who was desperately looking for her birth mother.

“I explained to her that the chances of finding her birth mother alive were low, as she would be over 90 years old. We finally found her, mother and daughter reunited after sixty-five years. In fact, the adopted woman brought her daughter with her to Greece, and the 90-year-old birthmother met her granddaughter,” says Van Steen with a warm smile on her face. She continues: “It is very moving to bring families together. Somehow, I also become a member of the family.”

Another story that has touched Van Steen is that of Maria Heckinger, who published her adoption memoir in a book called Beyond the Third Door (2019).

Maria was born of rape in Patras. Social taboos and the fear of public outcry forced her 17-year-old mother to leave her baby in the city nursery, and from there the child ended up in the United States. The two met several decades later.

However, there are still many Greek-born adoptees who keep trying to find their birth parents, but the nurseries where they came from deny them access to their files.

TWA, Cleo Lefouses

The aim of the Belgian professor is to persuade the Greek authorities to systematically examine the records of the 4,000 people concerned, to facilitate their reunion with their Greek birth families, and also to give them the Greek citizenship back, which they once had. “Officials from the Prime Minister’s office and from the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs have been in contact. I have expressed my desire to participate voluntarily (pro bono) in an organized effort to reunite the adopted children with their birth relatives and to help pave the way to a restored Greek citizenship (as a second citizenship). Significantly, even if their birth parents have passed away, these Greek-born people care to be recognized as Greek. My activism has made them aware that they are not alone anymore, as there are many others like them.” The campaign is rightly called “Nostos for Greek Adoptees.” She concludes: “Greece is always actively looking for ways to strengthen relations with the diaspora. At this time, the Greek-born adoptees of the 1950s and 1960s fervently desire to reconnect with their families. The time is right for Greece to take the first step to welcome them back!”

0 comments