THE DARK DAY OF THE DISTOMO MASSACRE BY THE NAZIS

About 100 miles roughly northwest of Athens lies the town of Distomo. Nestled in the foothills of the Mount Helicon, in western Boiotia, the town of roughly 3,000 resembles many of its bucolic sister villages that dot much of mainland Greece. But there’s something that belies this idyllic nature. For Distomo is the site of one of the darkest days in modern Greek history: the Distomo Massacre. It is where almost 80 years ago – on June 10, 1944 – 228 people lost their lives at the hands of the Nazis.

Modern day Distomo town with the Massacre Memorial

Yet, the painful saga does not end there. For the past 75 years the families of the victims have been waging a precedent-setting, international legal battle to seek reparations from Germany for their unfathomable losses. Needless to say, that battle has been wrought with legal red tape and the fine print of international law.

But, let’s go back to 1944…

In the spring of 1994 Germany was well into its third year of the occupation of Greece. At the time, the eventual withdrawal in October was not even a thought on the horizon. While they were enjoying the fruits of their occupation, they still had to deal with the Greek resistance, the most formidable in all of Europe. The residual effect of the Resistance’s relative success in undermining and upending German strategy in Greece led to a tacit “scorched earth” policy that endorsed the methodical killings of civilians.

This was no more grimly evident than on that June day in Distomo. A Waffen-SS company, part of the 4th Polizei Panzergrendier Division, presided over the Boitia region. The company, based out of nearby Livadia, had received reports that andartes had engaged in battle with German forces in villages nearby.

It is at this point the narrative becomes murky. Fritz Lautenbach, the captain of the company, was ordered to locate the attacking rebel fighters and engage with them. Apparently, as the company marched into the area, they came under fire from ELAS (the main Greek resistance group) and a skirmish ensued. The Germans had taken on several casualties. It is at this point where Lautenbach later claimed that it was at Distomo that they had come under fire and that a “savage reprisal” was necessary. Lautenbach then ordered Commander Hans Zabel to carry it out.

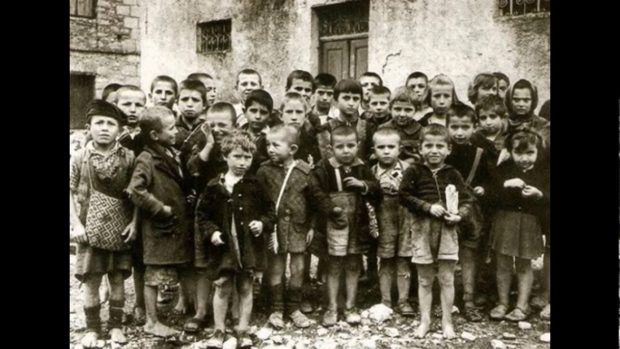

The Nazis marched towards the town. And what unfolded was an atrocity of unthinkable proportions. At first the Germans began shooting indiscriminately at anyone who happened to be in their way: men, women, children. They then began raiding house after house. It is at this point the horrors take another turn. Women were dragged out, brutally raped, stabbed and then killed. Children were shot point blank and infants had been dismembered. The local priest was beheaded. 228 people. 117 women. 111 men. Of those, 53 by most accounts were children. And then it was time to burn the village to the ground.

These events hit very close to home for Andy Sehremelis, a Southern California businessman whose own father, George Sehremelis, lived through those events. “My dad was out in the fields with my grandfather when the massacre happened. He was 8-years-old,” says Sehremelis. “But my aunt and uncle were in the village. The Germans would put ‘X’ marks on the doors of houses they had already entered. In the case of our family’s house a horse had been killed, and they used the horse’s blood to mark an X on our house. It probably saved them.”

It was the coming of nightfall that prevented the complete massacre of every single person in Distomo. The Nazis – fearing they’d come under ambush by ELAS under the guise of darkness – retreated and marched back to Livadia. What was left was the unbearable pain and horror of the surviving villagers.

But the impact of the massacre doesn’t end there. And the aftermath provided context that only magnified the tragedy. As mentioned earlier, Lautenbach claimed he came under attack from ELAS rebels in Distomo. Under pressure from the Greek collaborationist government, an inquiry was convened. At the inquiry a German secret police officer, who was traveling with the regiment, testified that the troops had come under attack at some place several miles away from the town. It was clear that the people of Distomo were innocent nonparticipants. Lautenbach defended his actions by stating he ordered the attack to “follow the spirit rather than the letter” of orders regarding reprisals. He even justified it as a pre-emptive attack. The tribunal cleared Lautenbach.

Furthermore, Zabel had fled to France after the war, but was arrested and extradited to Greece to stand trial on war crimes. In 1949 he confessed in a pre-trial that he was simply following orders from his superiors. But, through a legal snafu, he was temporarily extradited to West Germany to face other charges there. He never returned.

For close to 80 years the survivors and relatives of the victims of Distomo have waged an ongoing battle for reparations from Germany for the crimes committed that fateful day. This fight found a spark in 1997 when four relatives of the victims filed a petition for damages against the German government. The suit was first filed in the court of Livadia which ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and awarded them 28 million Euros in damages. The case eventually made its way to the Greek Supreme Court which upheld the ruling. The small victory turned out to be a “legal nothing” because any judgment against a sovereign state could not proceed without prior consent of the Minister Of Justice. Furthermore, the same families filed a petition with the German courts who, in 2003, rejected their claims primarily on the basis that Greece had no case over Germany because the acts were “sovereign,” and, under international law, Germany was immune from another country’s jurisdiction.

Undeterred, the victims moved to file their case in Italy where a legal precedent had existed for international war crime reparations. The Italian court ruled in favor of the victims and awarded them the right to German property held in Italy: in this case, a villa in Lake Como. By 2008 Germany filed a complaint at the International Court Of Justice in The Hague stating its immunity under international law. The case bounced back and forth in the Italian justice system and, by 2014, the Italian Constitutional Court rejected sovereign immunity as a defense for war crimes and destruction of property. And it has remained unenforced since.

But, despite the impasse of decades of legal wrangling, the survivors continued on with their lives. For George Sehremelis, it came in the form of the Red Cross that got him out of the village. And he found his way to America through an orphanage. There, he raised a family and started a successful business. But, in a strange but poetic twist of fate, his village never left him: “He returned to visit Distomo in June of 2016, and, in July, he died in the village,” says his son Andy.

On a hilltop, about half a mile from the center of town, resides the Distomo Memorial and Mausoleum. It is both magnificent and imposing in its size and architecture. There is an ossuary that holds the skulls of the victims and an external, marble wall on which the names of all who lost their lives are inscribed. And, in the center of town, there is the Museum Of Victims Of Nazism. It holds photos and historical documents from the events of that fateful June day. It is both a grim reminder of that tragic event and an educational source for all those who will affirm the words “never again.”

But, certainly Andy Sehremelis has done just as venerable of a thing. “I built a house in the village – a legacy home for my own kids and grandkids. To know where they came from and not to forget.”

0 comments