New Year’s Eve at Thio Stelios’

We were living in Brooklyn then, in the late 60s, and I remember for one New Year’s Eve my Thio Stelio invited us to his house to “play some cards and have some trella.”

Thio Stelio was my favorite uncle, then and now, and I knew everything he did would be fun. When I came from Greece with my yiayia back in 1960, he was the one who picked us up at the ship, the Queen Frederiki, in his big old American car—the first American car that one of my relatives actually owned, instead of being a taxi back in Greece. And he drove us all around Brooklyn to see the relatives, with my yiayia in her mantilla, and me in my short pants from Greece—fortunately, it was the summer–but who cared about anything when Thio drove us around in his own koursa and bought us ice cream from the ice cream store!

America was great, and Thio Stelio made it great!

Only then he put us on the train that would take us to my parents in Montreal, Canada, and I was a little disappointed: I thought Thio Stelio would be around forever to take us for rides and buy use ice cream and talk to me like I was his son—he wasn’t married then—and sing “Mandouvala” with me in the car with the windows open, which I had learned in Greece.

But he came to visit us in Montreal, in a two-toned Chevy, maybe it was a classic ’57—where did Thio get all his cars? Only he knew everybody, and everybody knew him, and he was always horse trading and doing business with one person or another. “Eh, he’s from across the lagada,” he would say about yet another of his friends or business partners, wherever that lagada was, somewhere back in Chios, for sure.

And we came to stay one summer in Brooklyn with him and his new wife, Thia Mary, and he drove a symoria of us to the beach one day in his Chevy Malibu station wagon that was powdered with flour from the donut shop he owned then, so we call came out looking floured, but we were going to the beach, so who cared? Me and some boy cousins rolled around in the back of the station wagon full of kefi and sang Kazantzidis and Perpiniadis and Yiota Lidia songs Thio was blasting from the little record player he had on his dashboard—a marvel of the time.

“Stelio, make it lower!” Thia would tell him, cause everybody was staring at these crazy Greeks, stuffed twelve to a car, blasting their crazy Greek music.

But Thio was a proud Greek, so he blasted it louder, with us singing from the back of the station wagon, and when some girls stared at us from some other car at a red light, Thio told them my name was Jimmy and I wanted to marry them.

“Thio–!” I said, and wormed myself under to hide.

“Ela, re, si—” Thio said to me, waving his arms like he was conducting a symphony orchestra. “It’s about time you got married and lost all your hair like me.”

Yes, he no longer had his Greek single-guy pompadour.

“Stelio’s hair fell out and I made a paploma,” Thia Mary teased him.

Now for New Year’s Eve, we were living back in Brooklyn, while my father worked in Chicago but came over for the holidays, and Thio Stelio had invited us to his house in Long Island, Hicksville, where he had moved, so we could spend New Year’s Eve with all the friends and relatives he had invited for the night: his house was always busy, anyway, but now we imagined there would be people spilling out of rooms and windows.

Tsiyaro and potio and poka, Thio had promised us, and then winked at me, like I was going to do tsiyaro and potio and poka, when I was still in 7th grade—but you never knew with Thio.

My father never played cards, but he was very good at counting everybody’s winnings, my sister’s fiancée never played cards, his last name was Michalakis, Mario, and he was a classic Michalakis: no tsiyaro, no potio, no poka, but he liked to have a good time, and he wanted to make my sister happy, and my sister wanted to have a good time, she was young and in love.

So we all packed into Mario’s mauve Rambler, the only car of its kind in Brooklyn, or anywhere–Mario followed his own passion–and we tooled along the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Long Island Expressway, with no Greek music blasting from the radio, Mario liked Mantovani, but we were all excited because we were going to have a wild night out at Thio Stelios’!

And just as we thought, when we got to his house in Hicksville, Long Island, all the lights were on, all the windows were open, and all you heard were Greeks talking loud, like they were all deaf, and every parking spot on the block had been taken with their cars, some with Greek flags and stickers, and the whole driveway spilling over with cars that were parked crooked on the lawn.

“Get ready,” my father said to us before we went in, because for teetotalling Michalakis’ to walk into a house with nothing but tsiyaro and potio and poka was a real challenge: what do you do with yourself?

But when we walked in, first the place was full of women and kids, the women carrying plates of food like harem girls from the kitchen, where Thia Mary was holding the big koutala and giving orders, the kids were running all over the house, thundering up and down the stairs, and then in the sala were the men, already having tsiyaro and pioto¸ and telling stories from their jobs and from the old country.

“Ella, Kosta, we’re telling stories!” Thio yelled to my father, cause my father was the great storyteller of the family, who knew every story about every choriano and had funny stories about all of them.

Like the one about the choriano who said he saw a whale devastating the countryside. And when his father told him whales don’t have legs and don’t walk on land, they swim in the sea, the choriono told him, Ella, yero, what do you know?

And there was the story about the mule outside my grandfather’s village store who wouldn’t let a choriano in the store because the man didn’t like the mule and the mule didn’t like him, so the man punched the mule on the head to let him into the store, but the mule had a head like an anvil, and he grabbed the man by the shirt and tossed him into the lagada, wherever that was.

And there was the story about the choriono who thought he was shrewd in business, so when somebody offered him 100 drachmas for his donkey, the choriano got suspicious and said, And why not 200? So the man selling the donkey said, All right, give me 200, and the choriono gave him 200 drachmas and boasted about how shrewd he was in business. Because nobody fools me, he said.

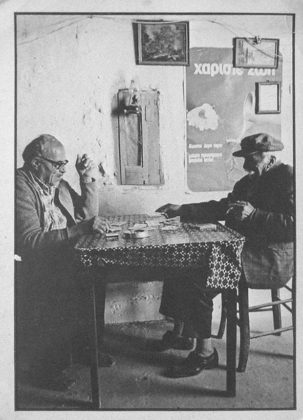

My dad sat down with the men and told all his stories, and everybody laughed, while the women traded family gossip, and food, and made sure the kids didn’t kill themselves, only then things got serious: because the poker chips came out, also the bag of fasolia when the chips and money ran out, and now the poka began.

While my father made sure nobody cheated, and Mario sat watching to be polite, and traded jokes, but he was engaged, so after being polite and manly, he disengaged himself from the men to be with my sister and the women and enjoy some Metaxa, which he would make an exception and drink for medicinal purposes: It kills the germs, he told me.

And I would stand and watch the men play cards, till the smoke would hang like a gray mosquito net, so then I would flee to watch cartoons with the kids in the den with the brown paneling and the sectional sofa; until the women joined us so we could see Guy Lombardo and those hazous Amerikanous, Thia called them, who were dancing with their party hats and blowing party horns at the Waldorf-Astoria and mugging for TV, with all their wives looking like Mamie Eisenhower.

“Just give us the younes and forget the kapella and troumpetes!” Thia said, cause most of the Mamie Eisenhowers were wearing their mink.

And it went on for hours: cartoons, old people dancing on TV, the men playing cards in a gray cloud, saying nothing except poker code, one word here and there about their hand, and their ante, and tossing chips and fasolia into the pot; while my dad kept a tally on a sheet of paper very neatly, drawing lines to separate the totals for the players, and I wondered how he could breathe in that cigarette haze.

Until the women made the men feel guilty because the ball was coming down and they were still playing cards, so the men stopped to stretch their legs and go to the bathroom, and then come and stand with their hands in their pockets to watch the ball drop; and everybody got sentimental and kissed and wished the New Year was better than the Old Year, but some said the Old Year was okay; and the kids were practically asleep by then, and the women wanted to go home, so some of the men began to disperse.

Cars got started and puffed with car exhaust and left, backing crookedly off the lawn, the house got suddenly quiet and you could hear the TV, but the poker game continued with Thio and the diehards, while I fell asleep on the couch watching an old Cary Grant movie, and my sister pretended she was watching it, too, but actually she was sleeping on Mario’s shoulder.

Until the last of the men left, with a big announcement about his wins or losses, Eh, it’s just money! he shrugged; and finally it was time for Thio Stelio and my dad to wander over, and Thio fall asleep on the sectional, and my dad plop in the recliner and watch Cary Grant and yawn, until it was time for us to leave.

“So now you’re going home—?” Thio Stelio woke up and told us and then winked at me. “Re, mikre, how much did you win at poka?”

I became a millionaire, I told him.

“With the fasolia?” he said.

And he grinned, and coiled an arm around my neck, and called me Jimako, and kissed me on the cheek, so I smelled the coffee and cigarettes and Metaxa and melomakarono on his breath, as he walked us to the door, with his arm still wrapped around my neck, and out to our car in his slippers, despite the cold.

And he stood outside in his slippers and waved as we drove off into the night, which became morning by the time we reached Brooklyn, and that was my one night of parelisia, when for a Michalakis I stayed up late and became a man, thanks to my Thio Stelio.

0 comments