- Leading HANAC: Stacy Bliagos on Community Service in New York

- The Hellenic Initiative Celebrates Record-Breaking Weekend in New York

- Building the Future: HANAC’s 53rd Anniversary Gala Honors Advocates for Affordable Housing and Community Care

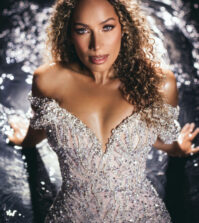

- Leona Lewis: Las Vegas residency ‘A Starry Night’

- Emmanuel Velivasakis, Distinguished Engineer and Author, Presents His Book at the Hellenic Cultural Center

“La Parisienne” Goes to the Opera: Maria Callas as Priestess

by Ilias Chrissochoidis*

“La Parisienne” is one the most compelling images we have from Minoan Crete (1400–1300 BC). Part of a larger fresco depicting a ceremonial procession, it was discovered in the palace of Knossos by Arthur Evans. The surviving head and upper torso of a priestess whose strong facial features are further enhanced with makeup, was so resonant with early 20th-century beauty standards, that she was likened to contemporary fashionable French ladies, hence the nickname Parisienne. Three millennia later, another Greek priestess, Maria Callas of equally striking facial details would associate herself with Paris, where she would die under sad conditions in 1977.

Cover photo created by Ilias Chrissochoidis, Ph.D., M.Phil., M.Mus. La Diva with La Parisiennefrom Knossos Palace

Callas owes her status as opera’s high priestess not only to her defining performances of the title roles in Bellini’s Norma and Cherubini’s Medea, but primarily to a set of exceptional qualities that make a great artist. She had a phenomenal vocal range, a prodigious memory, sharp focus, exceptional willpower and stamina for work, and, above all, religious devotion to her art. This allowed her to learn new roles in record time, to develop a huge repertory, to perform more frequently than any other of her colleagues for several years, and to generate extraordinary emotional responses from audiences all over the world.

Unlike her compatriot Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896–1960), whose religious devotion to music was matched by a saintly life of self-sacrifice, Callas demonstrated a schism between her stage priesthood and her personal life. Far too many witnessed her outside the stage as an unremarkable, even shallow, personality. Shyness and insecurity, lack of education, and trivial interests (home cooking) made her a rather awkward person for social interaction. On the other hand, those traits that made her a great artist were generating conflict and sorrow when applied in her private life. Devotion to her art was turning into possessiveness, domination, arrogance, jealousy, when it came to human relations.

To make things worse, Callas sustained and widened this chasm between the lofty artist and the suffering woman through false statements and pretended denials in the press. The public was kept in the dark regarding her failing voice (not to mention her increased dependence on sleeping pills and booster drugs). She constantly complained about being misunderstood and unfairly attacked. And her high-profile cancellations were all attributed to either poor health or inhospitable circumstances. She was never to be blamed for any adverse publicity. On the other hand, she had no problem manipulating those who could be useful to her. To overturn bad publicity in America, she befriended and got very close to gossip journalist Elsa Maxwell, exploiting the latter’s erotic infatuation with divine Callas. By presenting herself, both in public and private record, as a victim, Callas undercut her own credibility.

Maria Callas followed by Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, 1968

America, America

Born in the heart of Manhattan, in 1923, Callas was a second-generation Greek American. The Crash of 1929 and growing marital problems led her mother to repatriate with her two daughters in 1937. Transplanting a teenage girl from New York City to Athens was not easy. The shy, bespectacled girl invested all her energies in singing, and soon made her debut in the Royal Opera. Like other Athenians, she weathered the Occupation as best as she could, continuing her studies and performing for German and Italian troops. The latter being considered collaboration with the enemy in the explosive political climate after Athens’ liberation, she was dismissed from the Opera and left Greece in 1945.

The return to America was fraught with struggle and rejections, as Maria was turned down by several opera companies, including the Metropolitan. A string of occasional summer performances in Verona, the mentorship of legendary maestro Tulio Serafin, and the accidental meeting with a wealthy admirer and future husband, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, put her on notice as Italy’s most promising young singer.

The ensuing whirlwind of performances in the late 1940s and early 1950s rapidly expanded her fame and eventually opened the doors of La Scala in Milan. Her seven seasons in the world’s most prestigious opera house mark the peak of her career.

Luchino Visconti’s La Traviata in 1955 made Callas an international star. Although her American debut had taken place in Chicago a year earlier, the one at the Metropolitan Opera, in October 1956, is considered her artistic repatriation to America. To mark the occasion, TIME magazine ran a cover story on her. It was the beginning of a turbulent period for Callas.

La Diva with Spyros P. Skouras, 1/11/1957

Skouras

The most famous Greek in town by the end of 1956, Callas got the attention of Spyros P. Skouras, the legendary President of Twentieth Century-Fox (NEO Magazine, December 2021, 48–50). A personal friend of Mitropoulos, who was conducting Maria in Metropolitan’s production of Tosca, Skouras had been on the Board of Directors of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and was responsible for popularizing classical music through reduced price concerts at movie palaces (“Roxy Affair”).

“When Greek meets Greek anything can happen—and usually does. So when Maria Callas dined with the Spyros Skourases at Greenhaven last Sun. night, it wasn’t too surprising to learn that Skouras discussed with this great diva, who has garnered as much space as any movie queen, the possibility of making a 20th-Fox film if a strong dramatic vehicle can be found (with music natch!)—and Madame is trés interested…” [The Hollywood Reporter, 12/20/56, 4.]

In the following years, Hollywood trade papers would link Callas to a number of film projects, most notably The Guns of Navarone: “Maria Callas might make her film debut in a non-singing role as a Greek partisan in Carl Foreman’s ‘The Guns of Navarone,’ which Columbia will release.” [Variety, 8/12/59, 17.] “Is it just a coincidence, hmm, that Maria Callas will make her screen debut in Onassis’ native land, when she plays opposite Greg Peck in Carl Foreman’s ‘Guns of Navorone [sic]’ on the Grecian Islands in January?” [The Hollywood Reporter, 9/15/59, 4.] When she would finally shoot her only dramatic film, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ill-received Medea (1969), her performance would barely include her spoken voice.

Maria Callas and Elsa Maxwell, 1957

Onassis and operapause

Not accidentally, Callas began her affair with Aristotle Onassis, in late summer 1959, after a string of “scandals” that left her unemployable in Italy, fired from the Metropolitan Opera and a controversial figure in America. The affair has unfortunately become a smokescreen for the priestess’ early retirement from staged performances, her messy divorce from a man that was significantly responsible for her career, and her plunge into the treacherous waters of the international jet set. Onassis’ opportunistic marriage to Jackie Kennedy gave Callas a final blow. Her last decade in Paris was a process of steady decline, as neither the priestess could serve her neglected art anymore nor the woman could find fulfillment and happiness.

Despite the relatively short span of her career, Callas’ footprint in the history of music theater is as heavy and indelible as it could be. Her electrifying performances renewed interest in opera as Europe was trying to stand on its feet after a devastating war. And the rise of new media like television helped transform an opera star into a global celebrity. At the same time, however, this priestess of music was responsible for adulterating her art. After her golden year at La Scala, and still in her mid-thirties, she gradually allowed her personality flaws and human yearnings to override the diva, turning herself into a fashion model, a socialite, a member of the international jet set, and the subject of a Greek tragedy.

Efforts to see her as a suppressed woman who escaped the hierophantic robe of an artist won’t change the verdict of posterity. Callas will be revered as a high priestess of opera, while her flawed personality will recede into oblivion.

Selected bibliography

“La Parisienne Fresco,” Heraklion Archaeological Museum, https://www.heraklionmuseum.gr/en/exhibit/la-parisienne-fresco/

Renzo and Roberto Allegri, Callas by Callas: The Secret Writings of “la Maria” (New York: Universe, 1998).

Sophia Lambton, The Callas Imprint: A Centennial Biography (London: The Crepuscular Press, 2023)

Tom Volf, Maria by Callas: In Her Own Words (NY: Assouline, 2017).

*Dr. Ilias Chrissochoidis (http://www.stanford.edu/~ichriss) is a researcher at Stanford University, author, pianist and composer. He has edited Spyros P. Skouras, Memoirs (1893-1953) and has discovered dozens of historical sources on modern Greece in American archives (https://stanford.academia.edu/ILIASCHRISSOCHOIDIS/Modern-Greek-History).

0 comments