Unofficial Histories: 1821

Alexander Billinis

This past weekend we celebrated our ancestors’ Revolution against the Ottoman Empire with a parade down Halstead Street, in Chicago’s Greektown. The last time we were there, it was just my wife and I, but this year, my two children, clad in national costumes created by my wife and her good friend, rode on the St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church float.

I was proud, beaming in fact, to see my children, both of whom are Greek citizens (as well as US and Serbian) waive the Blue and White. Given my penchant for deconstructing, for knowing too much and asking too many questions, I could not help to think about the ironies of 1821, or any national revolution in fact. Every revolution, every war of independence, is also in some ways a civil war.

My son, John Billinis, on the St. Demetrios Float during the Greek parade in Chicago.

Take the American Revolution. When I was my son’s age, not (so) long ago, the American Revolution was portrayed pretty much in terms of right and wrong, and that all American colonists wanted the British out. Not true, not really. Nearly half of the colonists were loyal British subjects, or at least highly conflicted in their loyalties, and often enough the revolution evolved, particularly in the harsh back country, into a vicious civil war. Similarly, the Greek Revolution is characterized as a glorious rebirth of an ancient nation, rather than a haphazard rebellion of various interests, usually very much at odds with one another, and plenty of times fought to replace Turkish pashas with Greek ones.

Like the American Revolution, the Greek one was much of the time a civil war, where brother fought against brother, or neighbor turned on neighbor, based on economics, politics, or religion. No doubt the majority of Greek Christians wanted to be free of the Sultan, and had every right to do so, but to paint the revolution solely in terms of selfless heroism is simply a false “officialization” of history. Ditto the American Revolution, or pretty much any other momentous, glorified, and sanitized occasion.

My “own private 1821” is particularly interesting and, well, complicated. I am a Hydriot and a Peloponnesian, from the key battlegrounds of the revolution, and my ancestors were in the thick of it, and, apparently, on both sides.

Let me explain. Notwithstanding their Albanian linguistic background, the Hydriots were staunch Greek patriots, who sacrificed their ships and their fortunes for freedom, though not for central rule. They proved this, at the end of the Revolution, when they stormed the naval base of the provisional Greek government, on the island of Poros, and burnt to cinders a brand new, American built frigate, bought for the new Greek navy via a highly usurious London loan. “We Hydriots are a prickly lot,” a fellow islander exclaimed to me upon my reminding him of this episode, shrugging his shoulders.

Just across the straits, in the Peloponnesus, my maternal ancestors from Patras no doubt followed the kapitanioi of Archbishop Germanos, and fought in various bands against the Turks and each other in the course of the eight year struggle. Further south, my paternal grandfathers’ ancestors were either killed, converted, or escaped to Asia Minor.

My paternal great great great grandfather was Haralambos Meimetis, son of Omer, a Greek Muslim, and Argyro, a Greek Christian. My grandfather, Alexandros (Meimetis) Billinis, took his mother’s maiden name because Meimetis, a Hellenization or Albanization of the Turkish Mehmet, sounded too Turkish. My father had told me about our family’s supposed Muslim roots, and together we had even visited my grandfather’s village, Ano Kastania, on the mountain spine of the Vatika Peninsula, halfway between Monemvasia and Neapolis. Seven years ago, when we lived in Greece, I took my family up to the village again, and we huddled around a samovar with three aged villagers, and heard their version, the unofficial version of my family’s story. My paternal ancestor Haralambos was born a Muslim in the village, but in the course of the massacres of Muslims in the area, particularly after the fall of Monemvasia to the revolutionaries, he saved himself by convincing his would be executioners of his Christianity. His brother was not so fortunate.

In the course of several years working as a writer and journalist, and living in the Balkans, I managed to connect with more of my relatives from the Vatika, a beautiful, rugged yet gentle place, whose equally fascinating, tough but tender people have scattered to the four winds. After republishing a story about my grandfather, who perished in the Battle of the Atlantic in World War Two, a distant cousin of mine, Antonis Kourkoulis, solved the mystery of Haralambos.

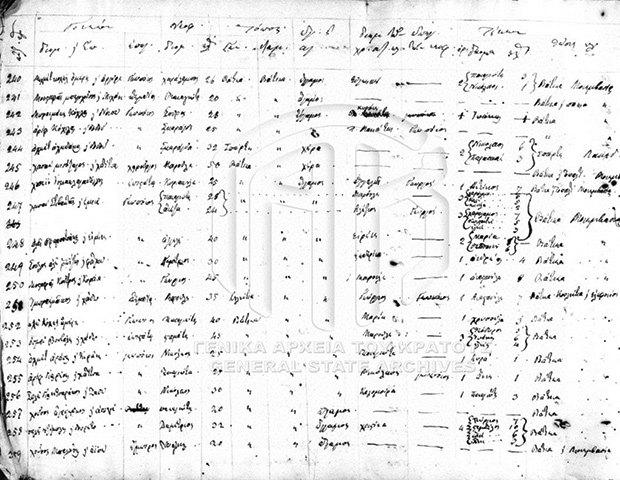

Plate from Greek State Archives

A document in the State Archives, one of countless, lists neophytes to the Orthodox Church in the year 1836, just a few years after the revolution ended with a sort of independence for Greece. One of the documents, handwritten, lists a 26 year old named Haralambos Meimetis, son of Omer and Argyro, as a new member of the Orthodox Church, and therefore, under the logic of the Greek State, a member of the Greek nation. What is clear is that Omer, his father, was a Muslim, while Argyro is clearly a Christian name. It shows that, contrary to national mythologies, local Muslims did exist in Greece and that marriages across religious lines were not uncommon. We do not know why Omer’s ancestors converted, or if by force, but the point is they existed. That my cousin went through mountains of documents at the State Archives, moreover, shows that such conversions were numerous, and are part of the private, forgotten, or redacted histories of thousands of Greek families.

For me, finding documentary, “official” proof that one of my direct ancestors was born a Muslim did not make me feel any less Greek. It did, however, remind me that we are all mosaics, that beautiful art form raised to its height, most appropriately, by our Byzantine ancestors. That most beautiful art form is comprised of thousands of parts, and each has value. It reminded me too, that we are all interconnected, most obviously with our neighbors, but also with humanity. When we celebrate wars and liberations, we should also remember that these shatter mosaics, as well as create new ones.

0 comments