Pammachon: A Martial Art and Ethos with Roots in Hellenism

Alexander Billinis

On March 25, this year, as every year, Greeks in Greece and around the world celebrated the dual holiday of Greek Independence Day and Annunciation. This time, it was different. We celebrated at home, via digital displays, or flag waving from balconies or verandas rather than crowding the streets of Athens, Thessaloniki, Melbourne, New York, or the smallest hamlet in Greece. God willing, next year, for the Bicentennial Celebration, we will all be out in force everywhere celebrating this holiday together.

Sequestration does have the advantage of more time to reflect, and as a historian and writer, I am as interested in the “how” of the Revolution as much as the “why.” It is a martial holiday, rooted in a martial ethos. It makes sense then, to examine this martial tradition and perhaps discuss its relevance to the present day. How did Greeks, over the centuries, fight successfully, and often against crushing odds?

Eric Hill, Pammachon Instructor and USA Program Director

The Greek martial tradition is thousands of years old. The most basic course in Western Civilization will make that clear, yet what is not obvious, but rather hidden, in plain sight, is a combat art with roots in antiquity with a continuity into the modern era.

Unarmed martial techniques are depicted in the Parthenon Marbles, codified in Byzantine war manuals, encoded in our Hellenic dances, and part of the common instruction for Greeks from time immemorial, fading out as Greece left the era of the 1940s and joined Modern Europe.

Luckily, there were enough of the old-timers around, for a few of the younger guys to try to assemble and, equally importantly, to contextualize this wisdom in the present day. Kostas Dervenis is a Greek-American engineer. Like many Greek-Americans, he visited his ancestral village often. His village, Papingo in the high mountain fastness of Epirus, for centuries has been an enclave of hardy, entrepreneurial types. In outings with his uncle, he was astonished at the older man’s strength and agility, where he showed the younger Dervenis how traditional methods allowed him to carry two 12-foot pine trees for six miles through harsh mountainous terrain. Beyond the wiry strength, there were the unarmed combat skills his uncle told him about and demonstrated.

Kostas was stunned to learn that martial education had been prevalent throughout Greece, incorporated into the Greek school system, between 1865 and the First World War. Vestiges of it survived throughout Greece until World War Two. For most of us, the elderly uncle’s display of strength would only be an impression. My father in law in Serbia, for example, had the stamina for physical labor in his seventies that I lacked in my forties, yet Dervenis knew too much about combat arts and body mechanics to leave it there. As fortune would have it, Dervenis repatriated to Greece in 1990 as the engineering manager for the Block 30 F-16 program, which gave him ample time to hone his research in situ.

What emerged was a (re)-discovery of martial art and ethos that had been widespread in the Balkan world in the early twentieth century, based on martial traditions hundreds or thousands of years old. Balkan villagers were able to leverage the collective wisdom of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine combat arts, “downloading” them into their dances and their exercises.

As the rest of Europe moved toward modernity, these “medieval” skills remained highly relevant in the Balkans—and remain so today. In a world of random violence, possession of martial skills and situational awareness remain vital. As Greeks, we are fortunate that such a skill set remains part of our cultural kit, provided we become more familiar with it.

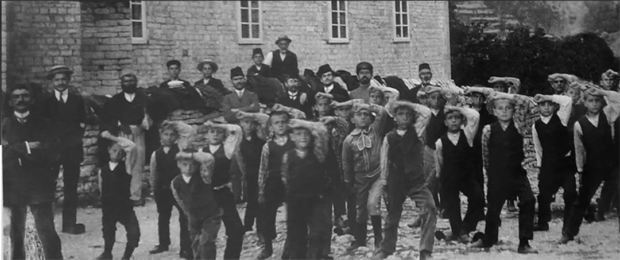

1905 Papingo practice-Kostas Dervenis, Headmaster of Pammachon

The pictures we have, of school-age children doing the simple yet effective repetitions that comprise this martial education method, have been found all over the Balkan and Asia Minor peninsulas, which meant that young Greeks had a drilled mental and physical skill in close combat arts before entering the army. It no doubt provided the small and poorly equipped Greek armies with an asymmetric power against their larger rivals. It explains their success in the Greek Revolution we eagerly celebrate on March 25 every year, as well as subsequent military prowess in spite of poverty and often crippling internal political dissention.

Lacking a formal name for these practices, Dervenis settled on the name “Pammachon”, reflecting an ancient combat sport prevalent in the eastern Mediterranean during the early Christian and Byzantine eras. A non-profit organization was created with the intention of propagating these teachings to Hellenic communities around the world. Over two decades of research went into analyzing 3000 years of continuous Hellenic history and martial records, so that their distilled essence could be incorporated into the eight movements and simple forms that make up the Pammachon method today.

As a historical footnote alone this combat art form, which survived into the present day and is encoded into so many of our dances is itself of interest, but its applicability to the present day is, in fact, more important. Pammachon is not simply a martial art. It encompasses a central philosophy, strategies, and wellness methods that have allowed our civilization to survive and often thrive where others have vanished. The art reflects a martial and spiritual code and ethos fully embedded in one’s own ethnic identity, and a direct inheritance of all the stages our culture has passed through in the course of Hellenic history. In an era where random violence occurs all too often, these skills remain as relevant in the present and future as they were in the past.

Certain lessons are timeless, and have passed the test of time.

0 comments