Searching for the historical St. Nick

by Katerina Georgiou

Somewhere in the commercialization of Christmas the truth about St. Nicholas was hidden. Over the years, the beloved Byzantine saint had been transformed into a caricature of himself. The transformation didn’t sit well with Andreas C. George, a radiation physicist with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and Department of Energy.

It all started one Sunday morning at St. Nicholas Church in Flushing when George learned that the small gold-and-jewel encrusted box on display contained part of the relics of St. Nicholas. “It was scientific proof,” said George, “that there was without question a real St. Nicholas.”

So when George eventually retired from his government job, he devoted himself to a new experiment: would following in the footsteps of St. Nicholas lead to the truth about the man and the meaning his life held? But researching a centuries-old figure for whom little information exists wasn’t easy, especially one that blends a real person—-St. Nicholas—-with a cultural archetype—-Santa Claus.

So when George eventually retired from his government job, he devoted himself to a new experiment: would following in the footsteps of St. Nicholas lead to the truth about the man and the meaning his life held? But researching a centuries-old figure for whom little information exists wasn’t easy, especially one that blends a real person—-St. Nicholas—-with a cultural archetype—-Santa Claus.

The facts are that St. Nicholas was born in the 4th century in Patara, present day Turkey. He was a well-known miracle-worker who later became bishop of Myra. His life was defined by charitable acts, particularly on behalf of children and sailors. Stories of his good works depict him carrying a bag of fruit to share with poor children and saving them from harsh fates. “He was like a modern social worker,” said George. “Always ready to help someone in need.”

Other tales recount how he helped sailors caught in storms. Sailors praying for St. Nicholas’ intercession often saw visions of him at sea and later recognized him when they came ashore. “Through prayer and divine intervention, St. Nicholas resolved bad situations,” George added. It’s for this reason that sea-faring countries like Greece embraced St. Nicholas as their protector and why they hang the “Timonieris,” or icon of St. Nicholas the navigator in their boats.

St Nicholas’ popularity transcended his death and people flocked to Myra to honor him. But in 1087 when the city was threatened by advancing Muslims, St. Nicholas’ relics were brought to Bari, Italy. “I don’t believe that the relics were stolen by the Italians,” said George, when asked about the ensuing debate over how the relics were relocated. With the relics safe from harm, the cult of St Nicholas spread further throughout Europe and his legend picked up steam all over again. Even when the Reformation swept across Northern Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, and icons and holy statues were destroyed, the image of St. Nicholas remained resilient.

Since his accessibility expanded beyond the Church—-St. Nicholas became not only a treasured presence in people’s homes and ships—-but a permanent fixture in their minds and spirits. But by the time St. Nicholas was introduced in the New World by the earliest Europeans settlers, cultural traditions had seeped into the legend. “In the Netherlands to honor “Sinter Klaas” (St. Nicholas) children used to put wooden shoes by the fireplace,” said George. “When the Dutch settled in the New World, the name Sinter Klaas was changed to Santa Claus.”

Once in America, St. Nicholas’ image was transformed yet again. His simple flowing robes were replaced by a red and white fur-trimmed costume. The sack of fruit was filled instead with toys. And his white horse was substituted for a sleigh and reindeer. As far as appearances go, the only thing that stayed the same was the white beard. Still, Santa’s metamorphosis wasn’t complete. In 1931, the artist Haddon Sundlon built upon author Clement C. Moore’s depiction of Santa, adding a plump belly and jovial face. This image, created for a Coca Cola advertisement, is the Santa we recognize today.

Despite St. Nicholas’ many transformations, one thing has remained constant: he has always been associated with helping people in need. “As long as we keep this in mind,” said George, “the trail left by St Nicholas’ footsteps is endless.” After all, it’s the meaning of his life and not what he looked like that’s important. “St. Nicholas lives on because he embodied the spirit of giving--an enduring human virtue that’s not limited by time or circumstance,” he said.

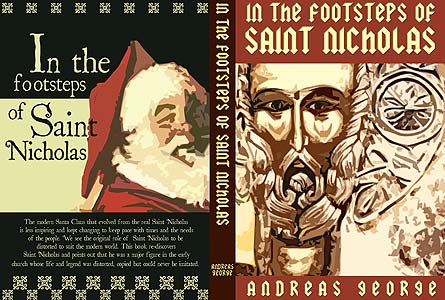

You can read more about George’s findings in his book, “In the Footsteps of Saint Nicholas (Seaburn Books, 2005).”