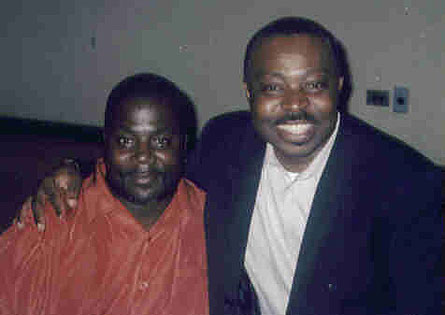

The most fervent philhellene

in New York - by way of Nigeria

A happy smile on his broad face, Sam Chekwas swings around the counter of his Seaburn bookstore in Astoria to ring up another customer: a 10-year-old boy purchasing an arcane volume by Paolo Coehlo. “Who’s reading this? You?” Chekwas asks. And when the boy nods solemnly, Chekwas is delighted. “That’s wonderful! You get a 10 % discount. And whenever you come in, ask for your discount. Okay?”

The Nigerian immigrant is delighted because since arriving in America more than a decade ago fresh from his studies at the Aristotelio University of Thessaloniki, he has waged the one-man campaign of a fervent philhellene to educate an entire generation of Greeks in both their modern and ancient literature and the American public to the glories of modern Greek and literacy. Through his bookstore and publishing company he has produced hundreds of volumes in Greek, English and Spanish, some featured on Amazon.com and at Barnes and Noble; through his lectures across the country he has tirelessly advocated the Greek language and culture (“Most people would introduce me as an ambassador of Greece,” he concedes in fluent Greek and English, sometimes both in the same sentence); and through his own writing he has contributed to the literature with books of poetry in Greek and English and an expanded autobiography chronicling his experiences as a student in Greece in the 1980s originally titled ELLEDA: TO ONIRO MIAS ZOIS and now called simply: THESSALONIKI, AGAPI MOU.

“It’s very hard when you love a language so much and a people so much to give an objective view,” he says, as he sits at a small table in the “Greek Section” of his bookstore in Astoria, surrounded by shelves of Greek dictionaries, monographs on Greek studies and the latest bestsellers from Greece. “It’s very hard to put into words all I feel about Greece and its history. It’s very deep.” Which is why he teaches Greek for free to the public at his bookstore (“Because I said by teaching Greek and reading with some other person it will make my Greek come back,” he declares) and why he still hasn’t given up the hope that despite some lukewarm responses from Greek Americans, he can continue to invite Greek authors to visit and read from their work. Maria Papathanassopoulou, best-selling author of O YOUDAS FILOUSE IPEROHA, and Lena Divani, author of OI YINEKES TIS ZOIS TIS, were among the popular Greek authors to visit his bookstore.

“My hope is to get the American public interested in Greek literature,” he vows. “These are wonderful books that can become international bestsellers. There is a book called MATOMENO HOMATA (by Didou Sotiriou), wonderful book, a novel, that if it was translated with a good budget, would sell four million copies. It’s so well-written, the story is so moving.” He also convinced the eminent poet Spiros Darsinos to translate his work in FROZEN HARPS, which is sold at Barnes and Noble. But, in addition, Chekwas has published more standard fare: a slim volume includes all 158 verses of Solomos’ national anthem, a series on  GREEK PROVERBS AND OTHER POPULAR SAYINGS by G. Pilitsis and J. Menounos, and he hosted a retrospective of Kazantzakis’ life and work, which included artifacts brought over by his adopted son. “The more people you expose to Greek literature, the more love you develop for the country,” he says. “Because that’s how I learned about Greece, through books.”

GREEK PROVERBS AND OTHER POPULAR SAYINGS by G. Pilitsis and J. Menounos, and he hosted a retrospective of Kazantzakis’ life and work, which included artifacts brought over by his adopted son. “The more people you expose to Greek literature, the more love you develop for the country,” he says. “Because that’s how I learned about Greece, through books.”

He was born in Nigeria one of eight kids to a businessman well-to-do enough to send all his kids to study abroad and Sam to boarding school, where at twelve he was exploring the books on his professor’s shelves one day when he discovered an English translation of Sophocles’ ANTIGONE.

“And I started reading and it made such a great impact,” he still says with rapture. “So I started looking for more.” Unfortunately, there wasn’t much more, unless he walked to libraries several towns away to bone up on his Greek mythology through forgotten volumes, but by 1980 he was smitten enough with all things Greek to apply to the Aristotelio in Thessaloniki and he was accepted.

“When you go to Greece, you imagine you’re going to meet Socrates in the street,” he laughs. “I was really disappointed.” He got the nickname “Papadopoulos” (who was in the news then) and because he didn’t speak Greek, he took intensive language courses with other foreign students in classes conducted by memorable teachers like Kyria Kofidi, who, he says, “had a love for her trade and made us love the Greek language.” Still, half the students dropped out, but the study of Greek only whetted his appetite for more. “I knew I came to study the culture and the language and the people,” he maintains. “My love for Greece was just enormous.”

He wanted to study philology, but a well-meaning professor advised him to also pick a trade, and so Chekwas graduated with a degree in dentistry, which he never practiced in Greece. But he did donate his 3,000 books to the library in Thessaloniki before he left Greece in 1986 and eventually joined most of his family in America, and he did write a letter to the minister of education proposing a $1,000 scholarship to a deserving African youth who “might turn into somebody like me,” he suggested.

Unfortunately, he never got a response, but when he came to America, he put his dentistry on hold (he served as a consultant to dental manufacturers) and he began spreading the gospel to the Greek diaspora. “I didn’t stop even one day preaching about Greece and its civilization and that’s because of the love from the people that I met in Thessaloniki and also from Greek letters,” he says (he still visits Greece every few years and has guest keys he says to at least three houses in Thessaloniki).

His fervor made him a celebrity in the Greek community and he was soon invited to speak at schools and churches, including the church in Rye, New York, where after his presentation, Archbishop Iakovos followed him to the microphone: “Samuel,” he told him, “that which you said, write it down for the children.” “So, actually, I thought that was a challenge and I sat down and put out the first chapter of ELLADA,” Chekwas says.

That sold 12,000 copies and while he worked to expand it, he realized there was no bookstore for Greek volumes.

“There was no place where you could come and find Greek books,” he laments. “And even if you don’t want to buy the book, just to see it, just to see what’s current. So it became something I really wanted to do.” He started Seaburn Publishing in a third-floor walkup in Manhattan and produced a hit in Jamaica with a coming-of-age novel called BIGHEAD, then opened his first bookstore on Steinway Street in Astoria, but he tried to cut in the competition on what he considered a mutual crusade to promote Greek literature.

“I had actually designed the shelves, to put them in every Greek store and fill it up with Greek books, so people wouldn’t have to travel,” he says. And while he ran the publishing company and the bookstore with his wife, Tyra Mason, he also teamed with a Greek partner to operate a dental and medical supply firm named after his old university, Aristotelio Dental and Medical Supplies.

“And I ended up educating Americans about what ‘Aristotelio’ meant,” he says, “because doctors would call--’Pardon me, what does Aristotelio mean?’ And I would spend an hour talking about Greece...Marvelous. I sent about 8 doctors to Greece just from that.”

With good humor, he also recalls the shock he gave some friends of his partner when he picked them up at JFK after their flight from Greece. “So here I am at the airport,” he says, “when I saw the four of them and realized who they were. And when I raised the sign with their name on it, you could see the surprise. One of them thought I was the driver,” he laughs. “So when I started speaking Greek to them, ‘Kalos oriste, paidia..., all of them stepped back,” he laughs still more.

Then he turns to listen to the tap of a customer at the door of the bookstore, and though the store is now closed, he gets up and unlocks the door for this customer and many other late arrivals. “For you, I open the door because I know you’ve been here before,” is his excuse. “A day doesn’t go without me reading a page at least in Greek,” he says, when he returns to the table and he glances around at the shelves with Greek titles. “Because it’s something that I wanted very much when I was younger. I didn’t go to Greece to get a degree, because I could have gone anywhere. I went there for a reason, and that was to know a little bit more about what Greeks are all about...And I’m searching here,” he concludes with his elegant and wistful smile.