Gallo winemaster remembers odyssey from Cyprus

By Dimitri C. Michalakis

His father Kyprianos was a distiller of ouzo and brandy in Cyprus and his mother's family owned vineyards. And when George Thoukis graduated high school it was understood that he would get into the business.

"But because he never had any higher education, my father felt I should have some scientific background to help him in his business," remembers George. "At the time, Cyprus was a British colony and we had a government enologist who had been to California and was very excited about the technology at the University of California. In fact, he had sent his son there to study chemistry."

So young George did the same. With his parents' blessing and savings, he left Greece and sailed to America on the U.S.S. America. He arrived in New York, didn't know a soul, and boarded a train for California. He got to Davis, California just as the Korean War was breaking out and he enrolled as an undergraduate student at the university while he picked peaches for $1 an hour to earn his keep.

"It was tough work, but it didn't bother me at all," he remembers. "I was nineteen and needed the money."

He spoke English, of course, because Cyprus was then ruled by the British. "They started teaching us English in our schools at the sixth grade," he recalls. "They were Greek schools, but the British financed the schools and they demanded we take as many classes in English as in Greek."

Thoukis graduated with his enology degree in 1953 from the University of California at Davis and was due to return to Cyprus. "But there was guerrilla warfare going on and I knew if I went back I would get involved in the struggle myself," he explains. When a professor offered him an appointment to graduate school and a job as a research assistant, he took it. "My God, and it wasn't even Christmas yet," he still marvels.

He went on to get his Ph.D. in agricultural chemistry (his research was on wine) and then was faced with the same decision of returning to Cyprus, when he was introduced to Ernest Gallo of the famous winemaking brothers (with Julio).

"And he said, 'What do you want to do? If you want to stay here, you might as well get a job,'" Thoukis recalls. "'With your science background, one of the best places to go would be the Gallo winery.' So I applied, and they accepted me, and I've been here ever since."

And in the 40 years since, Thoukis has risen to become a winemaster for Gallo Wines, the largest winery in the world, which produces one of every four bottles consumed in the United States ("We're big, but we're good," Thoukis emphasizes). He not only supervised the creation of Gallo table wines like Hearty Burgundy, but also the new crop of premium wines such as Turning Leaf, and his own G. Thoukis label.

And in the 40 years since, Thoukis has risen to become a winemaster for Gallo Wines, the largest winery in the world, which produces one of every four bottles consumed in the United States ("We're big, but we're good," Thoukis emphasizes). He not only supervised the creation of Gallo table wines like Hearty Burgundy, but also the new crop of premium wines such as Turning Leaf, and his own G. Thoukis label.

"Which is only distributed from time to time at some of the prestigious hotels, including Westin and Hilton," he explains proudly. "It's just for certain hotels that want to serve it by the glass."

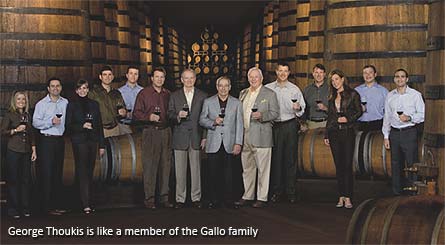

He worked closely with Julio Gallo for over thirty years ("He was like a father to me--tough as nails, but a fantastic person") and later worked closely with Ernest, who in his nineties still came to work every day. "In fact, I reported to him," says Thoukis, and adds with a chuckle: "He liked to have older people around him for comfort."

In the ‘60s, Thoukis offered his services to the Cyprus wine industry. “In fact, I think I wrote to Archbishop Makarios, who, when I was in high school, was our local bishop. They wrote me back: ‘Well, we have your letter, if anything develops, we’ll let you know.’ I never heard from them.”

He says about Greek and Cypriot wine: “I tasted some cabernet in Porto Karas and it was very beautiful, French-style. But on the average, they still pursue the local varieties that have been grown for a long time.”

The inheritance laws, however, are imperiling the future of Greek and Cypriot vineyards, however: “There has been this subdivision of land, so people have this very small piece of land, and it’s not workable. You have to change the inheritance laws to bring these small packages together, to establish a sizable 100, 200 acre vineyard. Then you could go out and buy machinery and equipment and make a living farming.”

His own knowledge of wine, he says, came naturally because, “Mediterranean people, including the Greeks, always have a glass of wine with their family meals. It’s no big deal. You drink it, it’s another beverage. Don’t get intimidated, don’t be afraid of it. The main thing is to enjoy it.”

As for being a Greek in the wine business: “For Greeks, wine is in their blood. Julio Gallo used to hire people and if their parents had any vineyards, he felt that was a good match. Because he felt it had to be in their blood.”

The Thoukis name, by the way, he explains derives from the historian Thucydides and was shortened over the ages. Talias and Thoukis was the name of his father’s distillery in Limassol, which is the center of wine production on Cyprus. Thoukis would help to bottle his father’s ouzo “and do just about everything.” When he returns to Greece now, he often drinks retsina like the natives, but rarely when he returns to America.

“Retsina is not really one of the famed wines of Greece,” he insists.